Since the start of the pandemic, the world’s 10 richest billionaires have grown richer while 99 per cent of the global population has seen income cuts. Evidence of the connection between the pandemic and rising inequalities is mounting. A new report by the European Trade Union Institute documents this trend and seeks to understand the structural nature of this inequality. We spoke with ETUI’s director of research Nicola Countouris who explained the findings and how policymakers might respond.

Green European Journal: A new report by the European Trade Union Institute looks at the impact of the pandemic on inequality in Europe as well as the steady growth of inequality in the longer term. How unequal is Europe today?

Nicola Countouris: The report captures both the impact of the pandemic on inequalities but also puts our understanding of rising inequalities into a broader context. I’m using inequalities in the plural because the pandemic has reinforced the view that inequality is not a monolith but has different dimensions.

Inequalities have grown in most European and OECD countries, for the past three to four decades. This analysis allows us to argue that, while it was entirely appropriate to deal with the pandemic with some strong anti-cyclical measures, these responses should be maintained as structural responses. In particular, the part-suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact should extend beyond 2022, state aid legislation should be reformed, and income support schemes should be revitalised to assist the “levelling up” process that Europe needs to embrace, especially in the context of the “twin” green and technological transitions. Some if not all of these “emergency” measures should be retained and we should also be thinking creatively about new redistributive policies. And it is not only a question of redistributing resources, as important as that is, but also redistributing power. Inequalities in Europe are a major democratic question, they are ultimately about power and voice. In this respect, mainstreaming industrial democracy institutions while curbing shareholder power are essential to the sustainability of Europe’s social, economic, and political integration.

The structural weakness of labour relative to capital also magnified the impact of the pandemic. Unfortunately, Italy will forever be associated with the pandemic due to the very early casualties it suffered. It is a real paradox that the epicentre of the first wave was northern Italy, one of the richest regions in the world. But we can now recognise that the productivism and presenteeism that are part and parcel of the north’s economic success also turned out to be its Achilles heel. This can be explained in part through precarity, lack of employment protections, and poor representation workers and trade unions in the workplace. It was only when Italian unions, in March 2020, called for industrial action, that social distancing and lockdown measures were finally taken seriously.

How do the different dimensions of inequality relate to the experience of the pandemic?

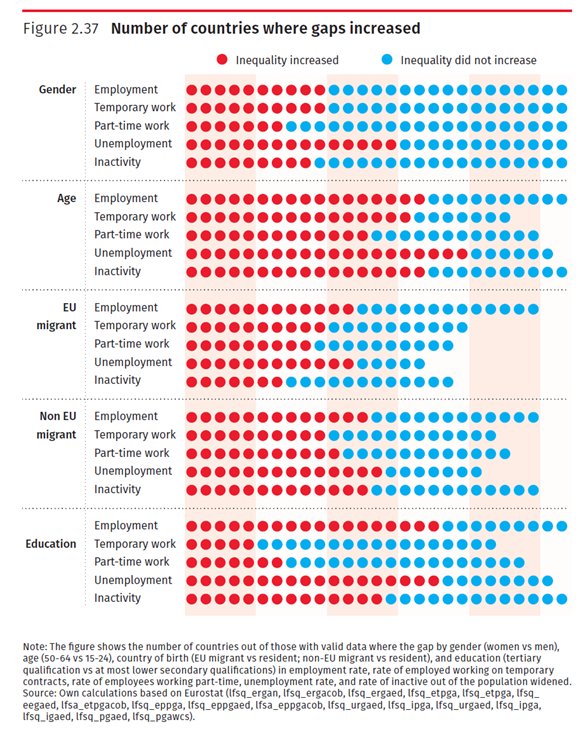

Not only has the pandemic magnified and exacerbated existing inequalities, but it has also thrived on them. From an epidemiological point of view, inequalities lead to worse health outcomes. Overcrowded accommodation and precarious working conditions that prevented workers from leaving the workplace when it was clear that they risked contagion exposed certain people more than others. The lack of resources and personnel in essential services such as the health sector was entirely predictable and increased the vulnerabilities of certain parts of society and certain countries both epidemiologically and economically – it was a Catch-22. [see data in chapters 2, 4 and 5 of the report].

The second dimension is that the pandemic has created new divides. The most obvious division that has emerged is based on whether or to what extent you can work from home. The disparate impact, including at a regional level, of this “teleworkability” divide, is captured very clearly in the report’s analysis of labour market developments [see chapter 2]. In every country, some jobs could not be performed from home, and it was the lives of these workers that were on the line. Furlough schemes and similar income support measures such as the cassa integrazione in Italy benefited over 40 million workers at the peak of the pandemic. These measures mitigated the impact of this divide and ensured that people who could not work from home kept their incomes, preventing the inequalities produced during the pandemic from reaching catastrophic proportions. However, the teleworkability divide remains significant. And again, some of the most precarious workers, often on bogus self-employment contracts, did not receive the support they needed, especially in some member states.

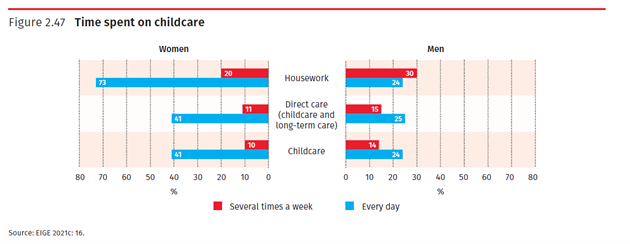

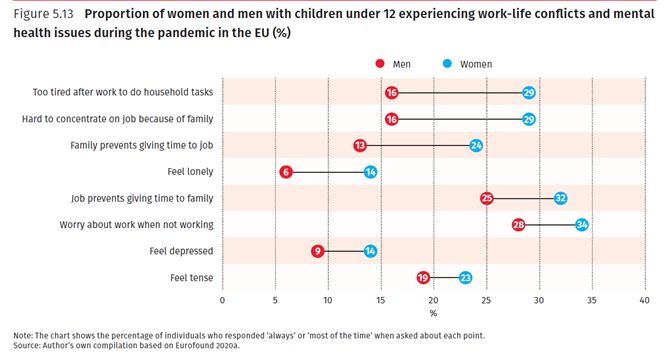

The third dimension is at the intersection of pre-existing inequalities and the pandemic. The impact of remote working on various demographics of our societies is markedly different. The clearest divide is between men and women. A much larger proportion of the female workforce that works from home is exposed to the stress and mental health issues caused by the dual burden of work and housework. The fact that the workplace has been collapsed into the home has had dramatic consequences for our societies that are deeply patriarchal in terms of the division of tasks in the household.

Socio-economic inequalities come into play too. Teleworking in a mansion and teleworking in an overcrowded house when schools are closed are two completely different experiences that will lead to completely different levels of productivity, and eventually could have a substantial impact on job and income prospects. We predict that this dimension will generate the most visible and deepest new levels of inequalities, unless it is kept in check.

What are your concerns around the future of remote work?

The future of remote work practices could go in any direction. For instance, we anticipate that a large share of the workforce that is currently working remotely under secure contracts of employment could be dramatically affected by a new generation of outsourcing practices. Just as physical distancing could replace the traditional workplace, contractual distancing could replace the traditional employment contract. After a while, remote workers could become remote sub-contractors. This could in turn lead to the “platformisation” of some services or their substitution by technology.

At the same time, many people have felt the benefit of greater control over their work location, working time, and even a chance to reflect on the purpose of their work.

One of the greatest and still to be resolved contradictions is that every time a workforce is asked whether they would prefer to continue to work remotely or go back to the office, they overwhelmingly respond in favour of working remotely or a mix of remote and office work. This might be starting to change relative to the early enthusiasm for remote working, but this preference still emerges from most surveys.

We can all recognise something positive about working away from the office. It’s clearly not just linked to avoiding overcrowded public transport or long commutes but is also about autonomy, taking back control, and agency. But then when you start to ask individual remote workers about their experience of managerial control, monitoring, and the blurring lines between private and working lives, seeing what has actually changed becomes more complicated.

Managers also realised that they were losing a certain level of control. The traditional methods of day-to-day management were evaporating and so they began to come up with new strategies. Managers will use all their available technological means to substitute physical control with technological control. There are clear indications that micro-management is increasing and that workers working remotely feel under increased managerial pressure. Working from home could be extremely liberating, but we still lack, and thus need to quickly develop, the legal or industrial relations frameworks that could rein in the tendencies towards surveillance, if we are to deliver on the promise of emancipation from subordination to the daily grind and entrepreneurial control.

Managers will use all their available technological means to substitute physical control with technological control.

To return to the Covid response measures, changes at the EU level were crucial to managing the economic fallout of the crisis in member states. The EU recovery fund is based on unprecedented debt sharing, and huge national spending was only possible because European debt rules were suspended. Should we think of these as temporary, one-off measures or as the beginnings of a structural shift?

Had it not been for the new approach to macroeconomic and fiscal governance at the European level, the situation would have been catastrophic for countries of the south, including Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain, all countries that had suffered disproportionately from austerity and whose automatic stabilisers were extremely fragile. It would have been terrible if they had had to pick up the bill on their own without the support that came through grants, loans, and changes to state aid rules.

In every crisis, there’s always a temptation to say that nothing will be the same again. It brings to mind Gramsci’s idea of the “interregnum”: that the old is dead, but the new is yet to be born, to paraphrase. But it’s probably not the right analogy for our time, because the old is not dead and is probably not dying. Some aspects of the old have been temporarily suspended but could return at any moment. Several countries prematurely stopped income support schemes in 2021, or drastically reduced them, and were then left scrambling because of the Omicron variant. There is also a serious risk that even the highly discredited austerity recipe that crippled Europe in the past decades could be revived at the end of 2022.

Another reason why the interregnum analogy isn’t appropriate is because it’s not entirely accurate that the new is yet to be born. There are new ideas – some of them have been implemented successfully over the past two years – and there is a lot of fresh, joined-up thinking going on around mitigating and even reversing our current, grotesque, levels of inequalities. In the context of tackling climate change, there is now a vast range of extremely compelling and highly credible alternative visions and recipes for changing our systems of production and consumption quite radically and drastically, veering towards a more sustainable future. So it would be unfair to say that these ideas aren’t born yet. We are instead in a strange situation where the old is competing with the new for legitimacy and resources. This will be the battle of ideas for the years to come.

The trade unions support a structural shift towards a more sustainable and fair economy, but they are also quite weak, historically speaking. On the other hand, there are far more progressive governments than a decade ago and different alliances combining the centre-left, Greens, Liberals, and the radical left are in power in many countries. Does the political situation provide grounds for optimism?

There is no room for complacency but there are some interesting signs. The most interesting aspect is that the redistributive policies that have been adopted in the past couple of years were not necessarily introduced by left-wing governments. Questions of inequality and redistribution are increasingly mainstream. One of the greatest proponents for reforming the Stability and Growth Pact is Italian prime Minister Mario Draghi, by no means a man of the Left. The longstanding demands of the progressive left have spread across the political spectrum.

Two structural aspects will also affect the development of the balance of power in the coming years. The first one is climate change. The old neoliberal mantra of TINA [“there is no alternative”] that shattered fundamental ideas about equality and solidarity is gone. But there is a new TINA, because there is no alternative but to confront the challenges emerging from climate change and the destruction of ecosystems. It is becoming increasingly clear that the longer we wait, the more difficult and radical the choices we will have to make will be. If we had started dealing with climate change 40 years ago, we could have just tweaked our systems of production and consumption. If we wait another 30 years, we will need a radical overhaul of the economic system.

Do we have credible solutions to address this existential challenge? I think we do, even if they will require radical industrial transformation, unprecedented degrees of public investment, changes in consumption habits, and extensive reform of the operation and financing of our welfare systems. The new, in that sense, is born. Most of these policies are not zero-sum choices but a few are. Those costs will need to be managed in a way that is just and fair. The transition will require fundamental changes to Europe’s productive infrastructure, with some highly polluting industries disappearing, along with the jobs they offer. There be important shifts geographically and between sectors. Anyone who tries to implement changes of this scale in isolation from workers and trade unions will find themselves in dire straits.

The most vulnerable in our societies are the most exposed to many of these changes and to climate change [see chapter five on occupational hazards]. They are also the least responsible for causing the problem in the first place – because they consume less. Inequalities will delay progress because these strata in our societies have much more to lose than many others because they have far less. This is one of the one of the many paradoxes of our unequal times [see chapter four]. The report also points to an additional paradox: that the growing levels of social and economic disadvantage are likely to hamper a decisive reorientation of our system of production and consumption towards a carbon-neutral future. In other words, since climate mitigation policies affect energy and food prices, they are likely to slow down progress in energy access and disproportionately affect the poorest, who spend a higher share of income on these goods, thus provoking resistance and discontent. It is because of this type of contradiction that we need to address inequalities in order to address climate change.

The transition will require fundamental changes to Europe’s productive infrastructure, with some highly polluting industries disappearing, along with the jobs they offer.

Where is social Europe in this discussion? Is the EU also taking steps to reduce inequalities?

The European Union has several regulatory instruments in the pipeline and their genesis predates the pandemic. Some of the promise of the European Pillar of Social Rights is finally materialising. The minimum wage directive, the directive on digital labour platforms, and directive on pay transparency, and the revision of the European Works Council directive will all be very important in terms of addressing inequalities. All of these regulatory measures have the potential to redistribute resources and strengthen labour law and workers’ rights.

At the same time, trade union and labour experts have been talking about these measures for over a decade, and post-pandemic we need to come up with something new to address the challenges that have emerged in the last two years. We need ideas and proposals for the next generation of measures that can reduce the inequalities that have been growing for decades.

Structural changes are needed to ensure a greater presence of workers and labour union participation in the capitalist productive infrastructure. Greater participation in the decision-making processes is necessary, and therefore we need instruments – partly new, partly updates of existing instruments – that reinforce the voice of workers in the capitalist enterprise. Worker participation should no longer be seen as exceptional but mainstream, across the whole of Europe.

We also need a new role, not just for labour, but also for the state. The small state is gone. There is no way we can face a challenge of climate change’s magnitude without a strong intervention on the part of the state, including through public spending. Redistribution channelled through labour rights and social security is important, but we need to talk more about the fair distribution of wealth and identify the new sources of wealth. Wealth is increasingly linked to rent and monopolistic positions within certain markets – this should simply be untenable.

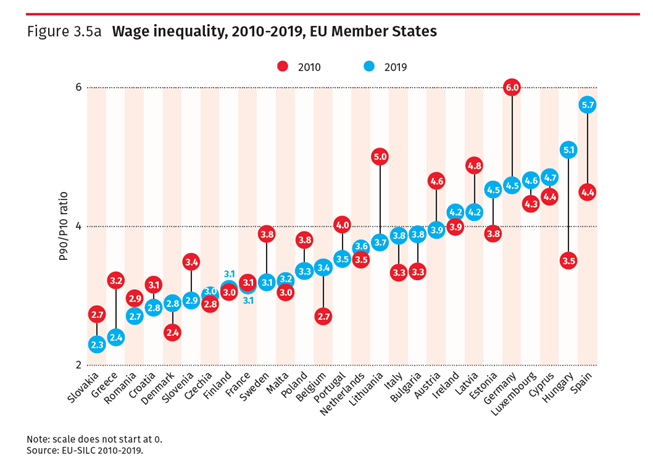

As the report analyses [see chapter three], the proposals at the European level are extremely important. The directive on decent levels of minimum pay has the potential to reinvigorate the trade union movement in member states where it has collapsed. It would also reduce the prevalence of poverty pay [wages too low to provide a decent standard of living] and the gender pay gap – by up to 30 per cent in some countries. However, we also need new measures, both pre-distributive and re-distributive, that reflect the new inequalities that have emerged from the pandemic and that allow us to tackle the great challenge ahead: climate change. Tackling climate change demands the redistribution of resources and power.