The recent elections in the Netherlands, which produced mixed results for the far-right and for the right, and saw the Greens gain many seats, appears to have been the nail in the coffin of the Dutch Labour party. What was the reason for this demise or does it represent a wider pattern and an opportunity that Greens can capitalise on?

A new political landscape has emerged in the Netherlands, one which seemed severely implausible even only ten years ago. A rightward turn has led to Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party (PVV) becoming the second largest party. A greater victory for the party was only prevented through the dual combination of Wilders’ ineffective campaign and the liberal VVD and the Christian-democratic CDA emulating his positions.

However, the real surprise is not the establishment of the so-called “populist” radical right of Wilders as a continuing presence – something already foreshadowed in the early 2000s by the late Pim Fortuyn – but the Labour party losing its central position in Dutch politics. What does this mean within the broader European political landscape at the moment, what does it say about the state of social democracy, and, consequently, what lesson should Greens draw from this election?

Labour’s loss

Whereas most international commentators focused on the limited electoral victory of Wilders and declared it a loss the real story of the election, the dramatic electoral loss of Labour (PvdA) was largely ignored. Suffering the greatest drop in Dutch parliamentary history Labour went from being the second largest party with 38 out of 150 parliamentary seats to having only nine. However, even national media did not look extensively beyond this fact and instead focused on daily politics after the election. When taking a broader look Labour’s situation looks even worse.

This election was the culmination of a series of electoral defeats since Labour’s victory in the last general election in 2012. The 2014 municipal elections already led to a mild electoral loss for Labour, leading to the first post-war city council in Amsterdam without social democrats. The following year during the provincial elections Labour lost in all 393 municipalities, losing around 40% of its representatives in the provincial legislatives.

Perhaps even more shocking than the aggregate election result for Labour this election is its local performance in traditional strongholds. In the traditionally social democratic cities of Rotterdam and Amsterdam they lost amongst others to the minority rights party DENK, a two-year-old splinter party from Labour. , the heartland of the labour movement in the Netherlands since its beginning in the late eighteenth century which has voted predominantly social democratic in every election since decades. This election Labour failed to secure a majority in a single district in this area, or anywhere else for this matter. A map of the results on the neighbourhood-level showed that Labour only managed to become the largest party in eight polling stations nationally. Indeed, the last time that the Labour movement represented six percent of the electorate was in 1905.

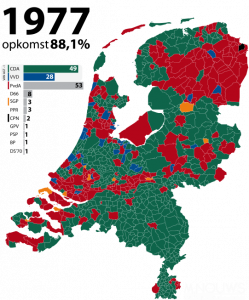

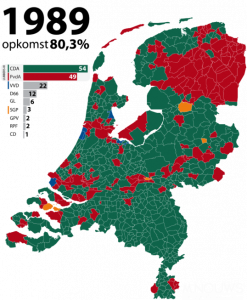

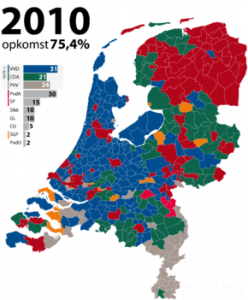

Within the context of Dutch politics this development in a way finds its parallel in that of the Christian-democratic movement. In 1980, post-war secularisation society forced the three largest Christian-democratic parties to merge. Though initially successful the party lost support in the 1990s, leading to the first fully secular governments. Their initial recovery during the 2000s ended with an electoral defeat in 2010 which, though smaller in size, was as dramatic a blow to the Christian-democrats as the current election is to social democrats. Since then the liberal VVD had increasingly become the largest party in the greatest number of districts whereas previously, even during the 1990s, the Christian-democrats dominated for decades.

The maps from 1977 to 2012 are by M. Nouws. The 2017 map is by a Wikipedia editor with the username RaviC.

Whereas the decline of Christian-democracy has been associated with a rise of centrist and centre-right liberalism the slide of social democracy seems to have led not to a wholesale shift, but to a fragmentation of the political landscape. Those who want to preserve the welfare state have drifted towards the Socialist Party (SP), Wilder’s PVV or the pensioners’ interests party while reformers were drawn towards either the Greens or the social liberals of D66. In addition, DENK’s (Dutch for “think” and Turkish for “equality”) emergence succeeded in drawing away the minority vote from Labour.

Though it is possible that Labour recovers in the next few years it is also clear that something is amiss within the Dutch social democratic movement. True to the left-wing tradition of infighting, in which Dutch Labour excels, the election result was followed by calls for prominent party members and officials to resign and withdraw themselves from the party. Likewise, pleas to dismantle the party – occasionally heard in the last few years – have become louder. The current Labour interior minister has even suggested a merger with the Greens, though neither Jesse Klaver, the leader of GroenLinks, or Labour’s leader Lodewijk Asscher were particularly receptive to this idea.

The European context

This election was cast in the international press as a crucial event within the current political climate in Europe. For this reason a great victory or Wilders would not just have been that, but also an event adding to the momentum of his radical right equivalents elsewhere. Regardless of the more complicated reality of the Dutch electoral result, Wilders’ electoral underperformance has led to a break in the dramatic structure of the political campaigns of the international radical right alliance.

Simultaneously, the tentative outline of a new counter-movement is beginning to take shape in Europe in the form of mobilising behind charismatic politicians such as GroenLinks‘ Jesse Klaver. Ironically, however, these elements are still very much fragmented and do not yet build upon each other’s’ successes. It was notable, for example, that the international relief after the elections mostly treated it as an isolated event and not as the second defeat for the radical right after Green Van der Bellen’s victory in Austria over the far-right FPÖ candidate Hofer last December.

Two things are noticeable about these self-styled opponents of national populism. First, their success seems to be correlated with a failing social democratic movement. The electoral fortunes of Van der Bellen in Austria, Klaver in the Netherlands, or Emmanuel Macron in France seem to be cases in point. This is not the case in, for example, Germany, where Martin Schulz seems to be succeeding in reviving the Social Democratic Party’s electoral significance, or – until recently – Italy, where Matteo Renzi seemed to be maintaining relative stability for his Partito Democratico.

Nevertheless, these social democratic revivals don’t seem to be based on a sustainable renewal of social democratic thought. The transition to a post-industrial society – which rendered obsolete the post-war corporatist welfare state – brought up Third Way politics as the new social democratic model. Today, however, there is as of yet no comprehensive social democratic answer to the challenges which we face in the post-2008 world of global turbulence.

Second, though not intimately associated with the establishment, the “anti-populists” do not have the anti-systemic ambitions of Greece’s SYRIZA, Podemos in Spain, or Jeremy Corbyn and Momentum in Britain. Indeed, it seems a legitimate question to ask whether they would, given the chance, contest the establishment when needed. Without addressing the establishment’s role in such issues as the radical right’s growing support, economic fragility, the refugee question, or climate change, it is unlikely that an effective response to them can be found.

It is in this space between establishment and anti-establishment that Greens can find opportunities in those countries where the social democratic movement is falling behind. Greens here have the ability to be a bridge between liberals on the one hand and the anti-establishment Left on the other. However, while the Greens are experiencing a series of breakthroughs in Europe, their position is still not a very strong one. When Greens do succeed in gaining political capital it will be difficult to maintain this support.

The demise of social democracy, a green opportunity?

In most of Europe the social democratic movement is facing exceptionally difficult times. Still, a collapse such as the one witnessed in the Netherlands is rare. Even more so than its sister parties, Dutch Labour was plagued by a political identity crisis.

While having supported quintessentially third way policies in the last four years, Labour presented itself as taking a leftward turn when the campaign started. Under the influence of the nationalist pull it expressed itself more culturally conservative, but simultaneously continued to cast itself as the party which stands for diversity. The result was a party which didn’t appeal to anyone.

However, Labour’s renewed left-wing rhetoric didn’t fit with their acts as coalition partner and were voiced more convincingly by the Socialist Party. On the other hand, the liberal VVD, and even the liberal opposition party D66 which supported the government on several issues, was much more embracing of the coalition’s policies. Likewise, Labour’s stance of “progressive patriotism” seemed hollow compared to the nationalist orientations of Wilders or the VVD and Christian democratic CDA, who have partially co-opted Wilders’ political orientation. On the other side, the minority rights party DENK provided a stronger guarantee of protecting the interests of these traditional Labour constituencies. Labour tried to please everyone and subsequently wasn’t supported by anyone.

Though there are additional issues specific to the Netherlands which contributed to Dutch Labour’s electoral fallout its inability to decide on a socio-economic and cultural course is a more common problem. It is characteristic of a movement which has lost its project: the welfare state. Indeed, it is in the Netherlands that social democrats embraced ditching the welfare state most wholeheartedly.

In a sense this course initially was a form of realism. In the face of the post-industrial disappearance of traditional working-class identity and the consensus on economic policy after the fall of communism, Third Way politics offered a way for social democrats to carry on with emancipatory politics. The acceptance of globalisation as a driver for prosperity which would render the classical welfare state unnecessary opened up space to focus on the non-economic themes associated with identity politics. Unforeseen was how these policies would engender domestic economic and cultural precarity – among both European minority and indigenous communities – and global turbulence.

Without a new general impulse which drives and defines the social democratic movement it will potentially cease to exist in certain areas, and already has in countries like Poland. This is not something which should gladden those on the Left as it seems associated with the growth of the Right instead of with a reconfiguration of the Left. Nevertheless, it also provides an opportunity for the Greens in particular.

The basic drivers behind the Left – a sense of solidarity with the vulnerable and a commitment to an equal and humane society – will continue to exist and be relevant in society. The quagmire has led to paradoxical positions and revivals which are likely to be only temporary. National populists attempt to profit from this by offering renewed stability through a return to a national approach in politics. Green ideas with regards to, for example, debureaucratisation, participatory forms of social policy and democracy, social and tax justice, the circular economy, and post-growth have the potential to blow new life into the Left. Along with Austria and, most recently, Finland, the Dutch general election has shown the time is ripe for Greens to assert these ideas as the core of the new Left.