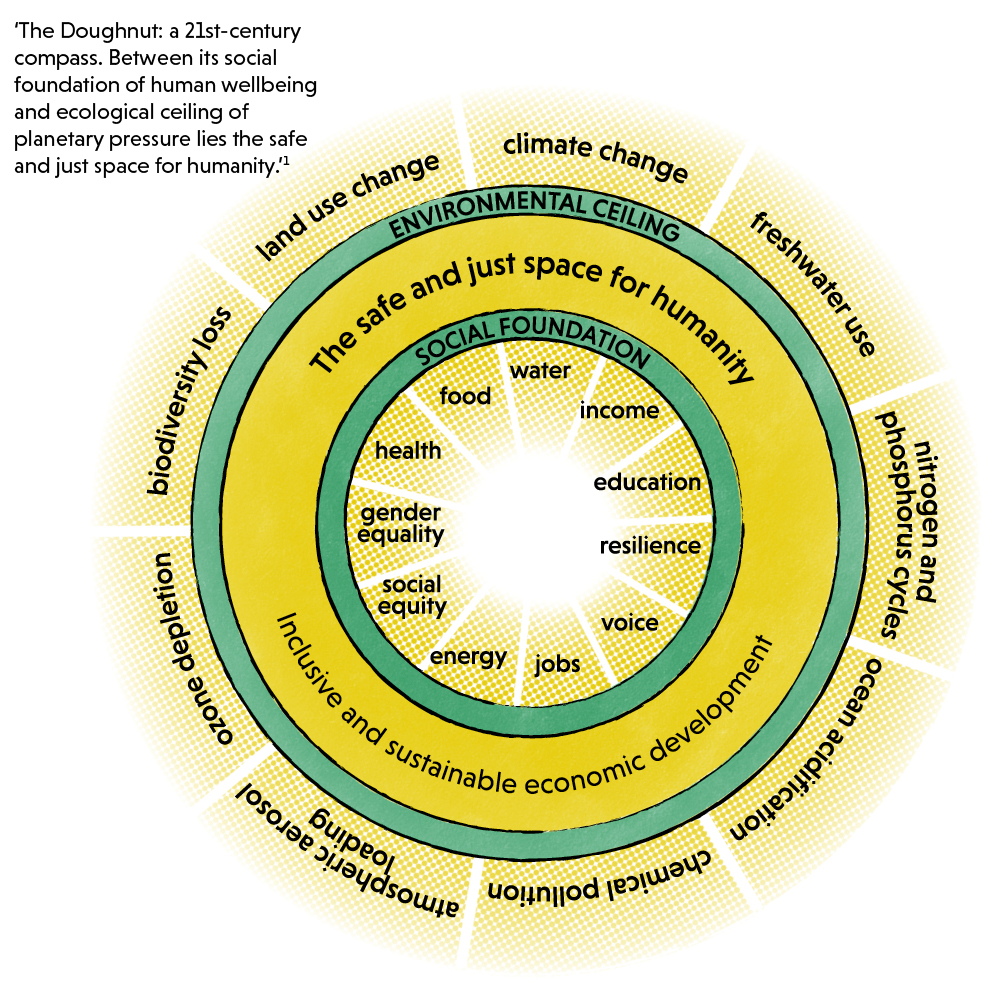

“What’s the silver bullet?” This is the question Kate Raworth hears all the time. As an economist and author of Doughnut Economics, her take on the steps society needs to take in the next 30 years is as simple as it is clear. “Bullets are for killing. I’m more interested in a golden seed. What do we need to plant so we can make the design of our institutions, financial systems, and economic framework regenerative and distributive?”

Tine Hens: According to Doughnut Economics, how do we shift our economic system so that it meets the need of the people within the means of the planet?[1]

Kate Raworth: We just do it. That’s how. We table the laws that need to be tabled. We start creating legislation and practices as if we actually believe we’re going to do this instead of endlessly talking about why we can’t do it. Take the financial system. It should be in the right relationship with the only set of laws we can’t change: the dynamics of the Earth system. We do not control the climate – we can change it, but we don’t control that change – we do not control the water cycle, the carbon cycle, the oxygen cycle, nor the nitrogen cycle. These are the given of our planet. We need to redesign all our institutions so that they are in the right relationship with the cycles of the living world and so that they are distributive by design. To change design, we need laws and regulation. That’s why Europe could lead here, with its power to set regulations across 28 – for now – countries.

What kind of regulation and laws are crucial?

Let me first explain why laws and regulation are key. Ultimately, economics is law. Not the kind of laws the neo-classical economists invented to prove that economics is a science as solid as Newtonian physics. The law of supply and demand, the law of the market, the law of diminishing returns: there are no such things as these fixed laws that underpin the economy. It’s just a kind of mimicry of how science works. Economics is a dynamic system that’s constantly evolving and so there are no laws, there’s only design. In the 21st century, this design should be regenerative, so that our material and energy use work within the cycles of the living world and within planetary boundaries. But it also needs to be distributive, so that the dynamics of the way markets behave don’t concentrate the value and returns in the hands of a 1-percent minority – which it’s currently doing – but distributes them effectively amongst the people.

Putting a price on fossil fuel can be a good tool, but it’s not enough. We must transform the basics of all production

So, coming back to your question, how are we going to get there? Through regulating the design of the economy. Neo-classical and neo-liberal economists are too focused on the price mechanism. Putting a price on fossil fuel can be a good tool, but it’s not enough. Ultimately, we must transform the basics of all production. And doing that is not asking the company accountants how they can optimise their tax position against some new tax or price mechanism. No, it’s forcing the company designers to review the heart of their process. Deciding, as Europe has done, to ban single-use plastics from 2025 or plastic bags as of next year is a clear-cut regulation and it will affect the core of the plastic and packing industry. Industry players can’t just recalculate their expenses, they have to redesign their bottles and reorganise their supply chain. The change law and regulations can bring is, in the long run, much more fundamental than what a price mechanism can do. If you want to change the world, you have to change the law. That’s becoming increasingly clear to me.

The European Commission published its vision for a zero-emission Europe in 2050. Let’s imagine this is the year 2050. What does our economic system look like?

Is this a world in which we win or lose?

That’s your choice.

I’m more interested in the world in which we win. So we’ve arrived in the thriving 21st century. The EU will have renamed and redesigned its policy department DG Grow into DG Thrive and economists will have woken up to complexity and will bring the language of system dynamics into their models, recognising that nothing is stable. The Stability and Growth Pact is seen as very outdated and has been renamed and rewritten as the Resilience and Thrive Pact.

Different EU departments would look at any incoming policy and ask, ‘is this part of a regenerative and distributive design?’ That will be the main touchstone: does this policy take us closer towards working and living within the cycles of the living world and is this policy predistributing the sources of wealth creation so that we actually create a more ecological and equitable society. Because all research we know of, even from the International Monetary Fund, confirms that in a highly unequal society the economy doesn’t thrive. I would like to see DG Thrive annually reporting on the doughnut concept showing us the extent to which European countries are putting policies in place that are taking us back within the climate change boundaries, reducing biodiversity loss, regenerating living systems, and reducing soil deprivation. I’m not expecting we will be there, but we’re clearly in the process of moving towards this point.

How would financial markets react to replacing DG Grow with DG Thrive?

First of all, we’ll put the money in service of the economy and the people instead of the other way around. Ownership and finance are crucial for the change and transition we desperately need. I call it the “great schism”. Often there’s this tremendous gap between the purpose of a company – most companies want to do good – and the interests of the shareholders, who I like to call “sharetraders”. It’s the schism between the 21st-century regenerative enterprise and the extractive, old design of the last century. If you’re owned by the stock market, by these pension funds or investment houses that are more concerned about fast returns on investment than about returns on society, it is just impossible to become a generative company that not only wants to do or be good, but also give back to society. I met somebody working in a pension fund. “I’m head of responsible investment,” she told me. “Well, who’s head of irresponsible investment?” I asked. “Me,” a man next to me said. One day, and I hope sooner than later, we won’t have that division anymore. Again: it comes back to the design of an institution. Finance is a design, money is a design, and there’s a power holding on to the design we have now because it means financial returns for a few.

Replacing ‘grow’ by ‘thrive’ is not just a matter of switching words, it’s rebooting the economic system, and also social security. How will we pay for welfare and pensions without economic growth?

What always strikes me with this argument is the presumption that social security is money flushed down the drain, so to pay social security always requires more money. That simply isn’t true. Social security is a redistributive mechanism. Because the ownership of the economy is so skewed, the worst off in society have almost no means to earn an income and they certainly don’t have access to the sources of wealth creation, so income is redistributed to make up for this system failure. But it’s not like recipients of social security are tucking the money under their mattresses; they’re investing it again in the economy to serve their most basic needs like food, heating, housing, and transport. It regenerates the economy from the grassroots, but the mentality that money we pay into social security is money gone has stuck. That’s the first thing we have to change.

Politicians still think they need growth to create jobs, but in fact it was passing dynamic.

But we have to dig deeper. Why redistribute income if the economy can be distributive by design? By enabling people to start small and medium enterprises, to be employees that have an enterprise share – like John Lewis in the UK does, although there are many more examples of employee-owned businesses – by enabling people to generate energy and found their own energy cooperatives. This is the unprecedented opportunity: distributive energy, distributive communication, the rise of open source – distributive design that has the potential to become a transformational way of producing goods and services where we predistribute instead of redistribute.

There’s another argument I’d like to debunk. It’s based on Okun’s law, another economic law that turned out to be more of a correlation and a passing dynamic than a law.[2] In the 20th century, there was for a very long time a tight relationship between a growing economy and full employment. Politicians still think they need growth to create jobs, but in fact it was passing dynamic. In many companies, an increasing amount of money created goes off to shareholders, while wages decrease. If Okun could see that we now have GDP growth and flat and decreasing wages, he would say, “I was wrong with my law, it’s a design.” There was indeed a moment in time where the returns of economic expansion would go to the workers, but now we’ve got shareholder capitalism. Many politicians today are over the age of 40. They had the same economic education that I got, which put the market at the centre and growth as the goal, there’s a long payoff of old economic thinking.

But isn’t this idea of post-growth or even degrowth very Western-focused? It’s quite easy to assume your economy should stop growing after reaching a certain level of welfare.

Sure. I lived for three years in Zanzibar, Tanzania, where there were many people living without shoes, without a toilet, without enough food to eat every day. Those people deserve and have the right to education and healthcare, access to mobility, and to feel their children will thrive. In the process of leading them to more thriving lives, I fully expect the amount of goods and services sold through the market to increase. A healthy market increases the goods and services sold, as should the commons. There should be an increase of technologies that enable households to thrive, technologies that enable women to need to carry less water and fuel. I absolutely expect their economies to grow and use more material resources. That’s precisely why high income countries need to get off the treadmill.

But I don’t desire their economies to grow indefinitely. That is simply not possible within the planetary boundaries. Nothing in nature grows forever, unless it is a mortal disease. All the countries of the world are somewhere on this growth curve. Some are ready to take off, others have landed. Countries like Zambia, Nepal or Bangladesh are desperate for growth to meet the people’s needs. They look at a country like the Netherlands or Belgium that live on astronomical incomes, and all they want is just to have more? This is evidence of the absurdity of the growth obsession: no matter how rich a country already is, the policymakers believe that the solution for every possible problem is still more growth. It’s nothing less than a sign of an addiction – a dangerous addiction. Because the social and ecological impact of a system that demands endless growth is, well, growing. It degenerates and runs down all the other parts of the system that make it possible to thrive in our personal lives.

What’s the reasonable possibility that changing DG Grow into DG Thrive will happen?

I want to be unreasonable. Reasonable is always rational. “Be reasonable, dear, don’t dream.” But we have to dream! Otherwise, they’ll always put us back into the box. It’s time to rise up and be unreasonable. There is every possibility it can be done. It’s about shifting mindsets and perspectives. Environmental scientist Donella Meadows, who wrote about system change, said, “Shifting the mindset is the most powerful leverage point.” On an individual level, it can happen in a millisecond. In the blink of an eye, the scales fall away from the eyes and we see things differently. Changing a whole society, that is something else. Societies fight like hell to resist a changing paradigm. That’s what we experience today.

The International Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 report made it clear that we have just 12 years to improve climate policies if we’re to reverse climate breakdown. Do we have time for system change?

Since the report came out, a lot people have brought this up with me, responding like rabbits in a headlight and saying, “We’re running out of time. We can’t aim to transform systems anymore. We have to stop being ambitious and work within the system as it is.” I think that’s dangerous. It’s a thought that can immobilise people with fear and despair. But it is also a tactic of many who resist change, denying the problem or putting it off until it’s too late to solve it. We’ll never get where we need to be if we suddenly grow pragmatic and don’t aim for an economy, institutions, and a financial system that’s regenerative and distributive by design. We can’t afford to aim for less.

This article (or interview) is a part of our extensive archive that traces the ongoing dialogue on postgrowth economic models, the politics of postgrowth, and the deeper significance of moving beyond the growth paradigm. You can find more essays and interviews on the “beyond growth” question featuring thinkers and activists such as Jason Hickel, Kate Raworth, Tim Jackson and Mariana Mazzucato on this page.

[1] Kate Raworth (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. London: Random House Business Books.

[2] Okun’s law holds that there is an inverse relationship between the growth rate of real GDP and the unemployment rate. For unemployment to fall by 1 per cent, real GDP must increase by 2 percentage points faster than the rate of growth of potential GDP.