As the world grapples with runaway climate change, growing inequalities, and a resurgent far right, the political establishment feels increasingly outdated. Progressive green-left coalitions must translate generalised discontent and polarisation into grassroots support for a bold climate agenda, providing global political and everyday societal energy solutions.

There’s a festering, yet completely normalised, form of dissonance in global (climate) politics. Every year the UN issues increasingly stark warnings of humanity facing “climate chaos” due to continued fossil fuel investments. Yet, governments from Greece to Guyana, and from the US to the UAE, maintain tired arguments of “energy security” and “market dynamics”, presiding over the largest expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure in human history.

While the Right drifts ever deeper into hyper-libertarian, anti-science, and conspiracy theory arguments to support its scaling down of climate policies, progressives (including social democrats and Greens) are not coming up with a convincing counterargument. Climate solutions – those that are not redistributive, do not address (carbon) inequalities, and do not adopt a cross-sectoral approach – are becoming increasingly harder to sell. As stark, increasing socioeconomic disparities plague even mature democracies like Germany and Sweden, the patience of voters is becoming razor-thin. This might help explain the rise of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), partly linked to a backlash against a law on heating, a flagship policy for the Greens that was hotly contested even within the ruling coalition.

What this far-right rhetoric fails to identify is the extreme carbon inequality that underlies our ongoing climate breakdown. This is not a coincidence: despite anti-systemic posturing, fascists and their ideology are the end products of (late-stage) capitalism – something which can be observed from Trump and Bolsonaro, all the way to Hitler’s Germany.

As the world veers closer to the precipice of multiple social and climate tipping points, reheated centrist, reformist 1980-esque politics just won’t cut it anymore. Slapping a meek carbon tax on private jets (that must be banned), or placing a one-off solidarity levy on multi-billion-dollar oil companies (that must be nationalised and dismantled), is not a convincing sell for citizens who are asked to change the way they heat their homes, commute to work, and eat.

Governments must start confronting the truth and scale of the climate catastrophe head on. They must be honest about how our climate models do not account for tipping points, given the latest climate science that highlights the “safe” carbon budget is actually much smaller than previously thought. Developed countries must radically step up emissions cuts (carbon neutrality by mid-2030s, well into carbon negativity by 2040s) to maintain even a modicum of organised society.

Global warming is accelerating at such a rapid rate that it is blindsiding the climate models of what were once the “doomsayer” scientists. What two years ago was considered radical (cue the IEA’s 2021 landmark report calling for an end to all fossil fuel expansion) is now already obsolete. In fact, the majority (60 per cent) of fossil fuel reserves must stay in the ground to have a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C. The IEA’s September 2023 report indeed highlights that existing fields and mines will have to close well before the end of their operating capacity.

A heroic act

It requires a bold and unwavering stance to admit and address this crisis. Governments must be equally forthcoming about whose fault all of this is – a politically daunting task. Calling out the military-industrial complex, fossil fuel companies, and the industrial agriculture lobby is a lot of eggs to break all at once. Equally, calling out the nihilism of moderate politicians, who dithered and delayed for the past 30 years, might break away from the decorum of respectability politics, but it’s the kind of populist, radically realist type of politics that enthuses, inspires, and, ultimately, garners broad, popular support. Remember Bernie?

Imposing bans and regulations by appealing to long-term goals like fighting climate change is the perfect fodder for far-right populists.

Let’s be very clear: we are not just stuck between nihilistically moderate politics and an emboldened, resurgent far right; there is a third way. The theory of “post-growth” presents a comprehensive set of ideas for moving the world beyond profit and economic growth to the pursuit of human well-being and environmental sustainability.

Is it an indigenous world understanding? Is it an activist slogan? Is it an emerging academic and scientific field? It is all of the above, and you would be excused for making tongue-in-cheek comparisons to a superhero – a powerful idea coming to save us from cartoon-esque fossil-fuel-capitalist-billionaire villains. Jokes aside, the power of post-growth lies in naming the sectors and practices we must do away with (industrial meat, planned obsolescence, the arms industry, fossil fuels), and opening a context-sensitive discussion on what we should aim towards (local citizen energy, community agriculture, publicly funded education and healthcare). Post-growth thus offers a springboard for left-green-progressive coalitions: a politics that is firmly confrontational in its articulation of what is wrong, yet simultaneously pluralistic, welcoming, and visionary.

A “militant” green-red alliance must also appeal to a broader more moderate audience, to build the grand coalitions needed for radical (political) change. Adopting a “people and planet over profit” vision is the first step. Translating these concepts into concrete actions is where the political gravity oscillates. Green policies must burnish their redistributive credentials, demonstrating how they lead to immediate economic relief and tangible improvements to everyday lives, thus rebuilding previously neglected alliances with workers and unions. In an age where extreme loss and damage are already costing billions to the EU economy (and, even more so, to the global economy), ecological economists must argue for climate policy as the only fiscally disciplined way forward – cue liberals and centrists.

Our latest issue – Aligning Stars: Routes to a Different Europe – is out now!

Read it online or get your copy delivered straight to your door.

Feeding back to the AfD and heating law example, experience shows that simply imposing bans and regulations by appealing to long-term goals like fighting climate change is the perfect fodder for far-right populists. A strong counter-proposal of social justice is needed. The good news? Addressing social inequalities concurrently with the climate crisis is a widely popular proposal, with a staggering 68 per cent of Europeans being in favour of such a dual approach.

In light of growing populist, and often defeatist, anti-climate rhetoric, civil society must loudly and unapologetically debunk the false dilemma that pits “climate” against “people”, and urge policymakers to adopt cross-cutting, intersectional climate policies. In light of the upcoming 2024 European Elections, civil society must demonstrate concrete actions that countries can take to concurrently address social and climate justice.

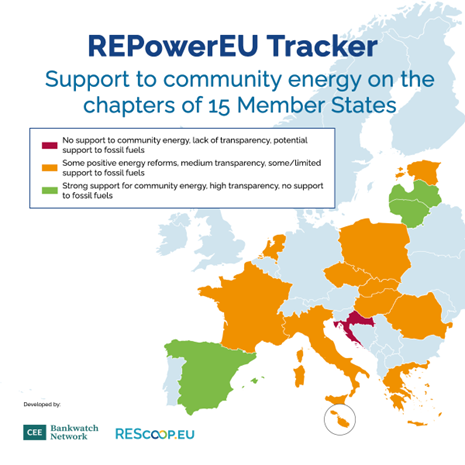

Solutions like energy communities can promote the faster uptake of clean energy, while reducing bills for households, especially the vulnerable, and building energy security. Despite the political grandstanding against “woke” climate policies, new analysis by REScoop.eu and CEE Bankwatch shows that countries are stepping up investments and reforms to accelerate clean energy. The analysis of the updated Recovery and Resilience Plans, including REPowerEU chapters, from 15 member states shows broad support for accelerated permitting, energy efficiency, and renewable energy. The many reforms and investments specifically around energy communities indicate that countries are taking the need to promote climate policies that are inherently socially just into serious consideration.

Democratic energy

Though mindful not to oversell any solution as a silver bullet, energy communities warrant particular attention. Explicitly functioning as not-for-profit entities following European Directives, they offer a practical articulation of the post-growth vision by prioritising social and environmental outcomes over profit. Energy communities thus not only inspire politically but also address everyday realities by co-developing actionable solutions. They are legal forms through which citizens, SMEs, municipalities and groups can co-own and co-benefit from local renewable energy projects. In producing energy locally, they offer cheaper, more secure access to energy for communities, shielding them from the volatile, for-profit, fossil-fuel-based energy market.

We are sitting on a powder keg of widespread social discontent.

The Energy Communities Tipperary Cooperative in Ireland offers a one-stop shop for citizen-led renovations, thus helping local people achieve deep energy savings and heating comfort. In Greece, the Minoan Energy Community offers free electricity to tens of households through medium-scale, local solar projects. Enercoop, a large cooperative supplier in France, adds a small levy to its customers’ electricity bills, which is collectively re-invested in renovations and other energy-saving measures for energy-poor households. In democratising production, energy communities address the yawning gap in modern “democratic” societies – there can be no real democracy without economic democracy, including direct control over food, energy, and material production.

Energy communities prefigure climate solutions that are inherently both socially just and redistributive. Bear with me on a thought experiment: what if the ambitious targets of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) were backed with 100% upfront, zero-interest loans (or grants) funded by innovative sources like a tax on frequent flying. Take the previous example in Ireland and reapply it: imagine placing a levy on the country’s top polluter (9.3 million metric tonnes of CO2 in 2022) and circling that money back into deep renovations for vulnerable households, facilitated by trusted community organisations like local Irish energy communities. The “make or break” element for climate policies is how relationally fair they are perceived to be. Which Irish citizen would accept a forced housing renovation conforming with the EPBD, or a meat tax for that matter (since industrial agriculture is the second elephant in the room for Ireland), if Ryanair continues to get away with carbon tax exemptions and fake CO2 offset campaigns?

We are sitting on a powder keg of widespread social discontent. Experts and civil society have repeatedly warned that the upcoming extension of the Emissions Trading System, which will cover transport and buildings, risks provoking a highly regressive effect, burdening vulnerable consumers. Shifting from a temporary band-aid approach of subsidising energy costs (which amounts to indirect subsidies for fossil fuels), governments are encouraged to frontload investments in structural approaches such as deep renovations, clean heating and cooling, and (public) electric mobility. These actions, enshrined in the Commission’s recent recommendations on energy poverty, are the type of foresight required to buttress European consumers from the persistent energy crisis.

Climate anxiety in check

As I write these words, Greece is enduring a heatwave stretching well into mid-November. Climate anxiety perforates my everyday life, stripping me of joy, excitement, and purpose for the future. What is the point of anything if everything is going to burn anyway? If only we could trade fungible “we told you so” moral-gratification tokens to make up for the decades of establishment inaction, perhaps I could recuperate all that lost serotonin.

We have never before veered so close to catastrophe and utopia simultaneously.

In the absence of market solutions to solve the creeping rise of climate anxiety, especially among young people, we need to build up alternatives, rapidly. The solutions are there, and most of them are already cost-effective. The European Environmental Bureau highlights that if half of fossil fuel subsidies for heating were redirected to heat pumps, Europe could achieve a decarbonized heating system by 2040. Even when the upfront costs are very high, as in the case of (community-led) district heating projects, public national and EU funds could de-risk the first stages of project development. The Netherlands is a case in point: a multi-million public investment fund is being set up, which will be administered by the community energy organisation Energie Samen, to establish locally owned, renewable district heating projects.

We are “blah-blah-ing” ourselves towards an abysmal cliff of climate tipping points, self-reinforcing earth system feedback loops, and widespread social upheaval. We need broad political coalitions that can translate this sense of urgency into a convincing, populist narrative that excites, angers, enthuses, and, above all, connects. The glacial progress of international politics in addressing climate and socioeconomic crises feels all-encompassing. Yet, across the world, a multitude of intangibles is taking root: eco-socialist ideas; beyond growth concepts and theories; horizontal ways of organising such as energy cooperatives.

I do not know if this is what keeps my climate anxiety in check, feeding me the much-necessary hope and drive to continue. Maybe it is just raw anger against a cannibalistic system pulling apart the fabric that weaves life systems together. What matters is that we have never before veered so close to catastrophe and utopia simultaneously, and in these trying times our vision and conviction should remain resolute: from a strong internationalist perspective, European progressives must unite in pushing for a (global) Green Deal with practical, community-rooted solutions that genuinely leave no one behind.