Following the European Parliament’s approval, the European Commission is pressing ahead with its plans to classify fossil gas and nuclear as “green” energy. This disastrous move will have repercussions on a wide range of issues from the war in Ukraine to the climate crisis in the years ahead. Seden Anlar looks at how the controversy has unfolded so far, and the impact it has had on the EU’s unity, climate leadership, and geopolitical strategy.

On 6 July 2022, members of the European Parliament voted to back the European Commission’s taxonomy proposal, thereby giving a green light to labelling fossil gas and nuclear as “green” energy resources and activities. It was a catastrophic result which, in simple and practical terms, means that fossil gas and nuclear investments will be considered green by the European Union as of 1 January 2023.

Behind the boring name, the EU Taxonomy Regulation sets out a classification system created to provide businesses, investors, and policy-makers with guidance around sustainable financial products and energy resources. The main objective of the act is to direct capital towards activities the Commission deems environmentally sustainable. In other words, the taxonomy was designed to address greenwashing by identifying those economic activities which are sustainable as well as by introducing reporting obligations on companies and financial market participants.

While the main part of the Taxonomy Regulation which established six objectives entered into force on 12 July 2020, the Commission announced it would introduce the actual list of environmentally sustainable activities through “delegated acts” later on. This decision was heavily criticised by EU lawmakers as delegated acts are secondary legislation in nature and thus would not be subject to the same level of ministerial and parliamentary oversight as the regulation itself.

In April 2021, the European Commission published the rules governing the taxonomy, but it delayed deciding on whether fossil gas and nuclear power should be included in the list of sustainable economic activities. Months later, moments before midnight on New Year’s Eve 2021, the Commission issued a draft proposal labelling them as “green” sources – a move that turned into “one of the biggest controversies” of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s mandate so far.

Our latest edition – Making Our Minds: Uncovering the Politics of Education – is out now.

It is available to read online & order straight to your door.

A divided union

In autumn 2021, the Commission started consulting with member states on the draft proposal which kicked off months of heated debates and negotiation. Two groups with opposing stances on whether the EU should label fossil gas and nuclear power green formed on an informal basis, led by two major actors: France and Germany, highlighting the strong divergence between the countries when it comes to energy targets.

France, which gets about 70 per cent of its power from nuclear, supported by member states from eastern and central Europe such as Poland, wanted von der Leyen to include nuclear power in the taxonomy. Germany, on the other hand, which shuts down three of its six nuclear power plants in 2021 and aims to close the remainder by the end of 2022, lobbied against the inclusion of nuclear and suggested adding fossil gas as an alternative. The country’s traffic light coalition government is split on the issue, however, with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in favour of fossil gas and Greens opposing the move. Moreover, during this process, anti-nuclear states such as Austria and Luxembourg showed their teeth by threatening potential lawsuits if nuclear power was labelled green. In the end, Germany and France have “agreed to disagree” and even denied the existence of any conflict. The Commission’s subsequent decision, officially announced in the Complementary Climate Delegated Act, to include fossil gas and nuclear power in the taxonomy clearly demonstrates the considerable influence of member states over EU institutions in decision-making.

This is how a promising initiative with the potential to contribute to the EU’s climate goals became yet another diluted component of the European Green Deal and a tool that will be used for the very thing it aimed to tackle: greenwashing.

Coming up short

Before the July 2022 vote in the European Parliament, MEPs had already been given the opportunity to react to the Commission’s proposal. The delegated act appeared to have suffered a major blow earlier in June 2022 when two of the European Parliament’s most significant committees, the Economic and Environment Committees, voted to block it, asking the Commission to come up with a new proposal. Such votes are usually an accurate indication of which way the plenary vote will go, but that was not the case this time.

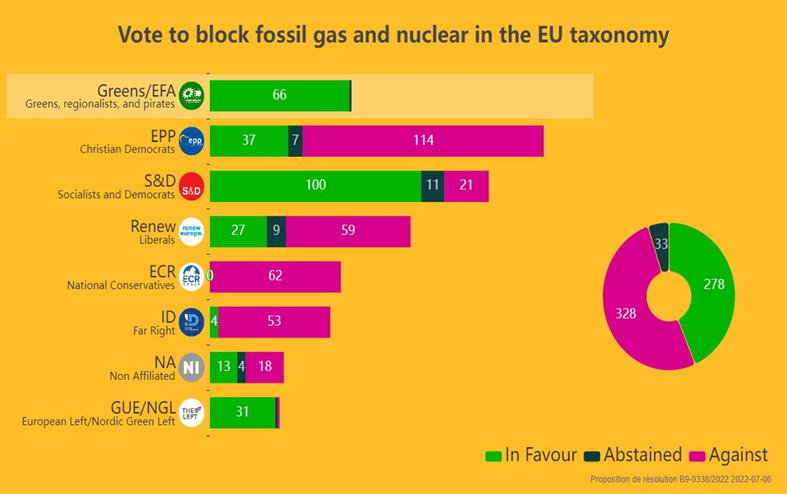

There has been opposition to the move, however. Since the Commission announced the controversial proposal to include fossil gas and nuclear in the Taxonomy Regulation, a cross-party and transnational alliance of MEPs against the proposal came together – a rare occurrence. When the main plenary vote was held, 278 MEPs from across party lines voted to block the proposal, 75 short of the 353 votes needed to secure the absolute majority required. However, since an absolute majority of 353 votes was needed, the opposition came up short.

Most of the MEPs who approved the taxonomy as proposed were from the centre-right European People’s Party, while the Greens/EFA were the only party that voted unanimously to block the proposal (with one abstention).

A flawed design

A binary classification that distinguishes good “green” energy from all other sources cannot allow for the nuanced approach that a transition that is both ambitious and realistic demands.

As the European Platform on Sustainable Finance expert group stated in its final report, this approach overlooks the intermediate activities that could be utilised for a certain period of time during the transition process. Moreover, the taxonomy leaves a wide range of resources that do not have a significant environmental impact unclassified, which could lead to investors seeing them as “not sustainable”. With European companies obliged to report on the sustainability of their investments, it is likely that any activity excluded from the “green list” will be perceived as not in line with the EU climate goals, which can dry up the capital that could go towards those activities.

Far from the science-based classification that it was supposed to be, the taxonomy shows outright disregard for what the scientific community has said must be done to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. Coming only a few months after IPCC’s warning that the planet might be on track for temperature increases up to twice the limit set out in the Paris Agreement, the actions of the European Commission and Parliament are nothing short of shameful. Moreover, such a taxonomy also dismisses the climate activists and NGOs who have called for the EU to take serious action to meet its climate goals. It is yet further proof that when vested interests are involved – business comes first.

Most of the criticism towards the expansion of the taxonomy has focused on gas, and rightfully so. While EU officials imply that gas is not as bad as coal – hardly the most reassuring talking point in the middle of a climate crisis – new investments in fossil activities like gas-fuelled power plants are simply not in line with the EU’s climate goals. Gas may be cleaner than coal, but it is not clean enough to merit continued investment in gas infrastructure. This was recently confirmed by the International Energy Agency when it stated that fossil fuel investments would have to be halted from 2022 onwards to keep global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius.

When it comes to nuclear, it gets a bit more complicated. While it may be regarded as an emissions-free fuel, unlike fossil gas, the life cycle of nuclear power plants including the construction, uranium extraction, transport, and processing releases significant amounts of CO2. Moreover, the construction phase is highly expensive and too slow, certainly to contribute to short-term emissions reductions and the 2030 climate goals set by the EU. While France strongly backs nuclear power as its beloved energy resource for electricity, even the financial label of the French government does not consider nuclear a sustainable investment. Funnily enough, the European Commission Vice-President responsible for the European Green Deal Frans Timmermans has stated publicly that nuclear cannot be classified as green. Finally, there are concerns that the inclusion of nuclear power as a green activity could divert capital away from renewables, despite renewable energies being cheaper than nuclear and gas, ultimately slowing down the energy transition.

The International Energy Agency stated that fossil fuel investments would have to be halted from 2022 onwards to keep global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius.

It’s the investors criticising the proposal for me

Unsurprisingly, some investors welcomed the inclusion of fossil gas and nuclear power into the taxonomy. The managing director of Germany’s local utility association VKU called it “an important sign of the role of natural gas as a bridge to achieving climate goals.” However, an unexpected amount of criticism towards the expansion of the taxonomy actually came from investors themselves and other stakeholders in the energy and finance industries, who voiced their concerns over the credibility and usability of the current version of the expanded taxonomy – signalling that they might treat the decision with caution or even boycott the new green labels.

For instance, the Net Zero Alliance, a group of 73 institutional investors, stated that the inclusion of gas “would be inconsistent with the high levels of ambition of the EU taxonomy framework overall.” Stephan Kippe, head of ESG research at Commerzbank AG also concluded that the approval of the Commission’s proposal “doesn’t make the fight against greenwashing any easier.” Hugo Gallagher, a senior policy adviser at the European Sustainable Investment Forum (Eurosif) also spoke out against the proposal saying, “Whether gas and nuclear genuinely meet the conditions for being qualified as a transitional activity is doubtful,” adding that many industry actors would not invest in gas or nuclear.

Fossil fuelling Putin’s war

Activists have been very clear that in addition to worsening the climate crisis, the expansion of the EU taxonomy will have a crucial impact on the war in Ukraine. Allowing more investment into gas and nuclear makes it harder for Europe to secure energy independence from Russia. The decision is therefore a gift to Putin that will ultimately continue financing his war machine.

The EU has already paid 57 billion euros to Russia for fossil fuels since the war started as imports of Russian fossil gas, gas turbines, uranium, and other nuclear services have been exempted from the sanctions imposed by the EU on Russia in response to the invasion. According to a new Greenpeace study, Russia is expected to be one of the main beneficiaries of the expansion and would earn an extra 4 billion euros per year thanks to the expansion, adding up to 32 billion by 2030.

When it comes to nuclear power, Russian state company Rosatom is set to “secure a share of an estimated 500 billion euros of potential investment in new EU nuclear capacity.” After pledging to stand by Ukraine, why would the European Commission and the Parliament hand Putin such an incredible geopolitical advantage on a silver platter (or rather, a uranium glass platter)?

Lobbies, lobbies, lobbies

Recognising that they would be the biggest beneficiaries of such an inclusion, Russian companies Gazprom, Lukoil, and Rosatom lobbied intensely in Brussels for fossil gas and nuclear energy to be added into the EU Taxonomy as green resources and activities. Greenpeace revealed that commissioners and senior officials of the European Commission had met with representatives of these companies a total of 18 times, either directly or through company lobbyists and subsidiaries since March 2018, when the Commission introduced its action plan on sustainable finance. The contrast between the European Commission’s actions and its public statements regarding Ukraine, such as von der Leyen’s declaration to Ukrainians during her visit that “Your fight is our fight. … Europe is on your side” in front of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, is simply mind-boggling.

It is important to note that the European Commission itself recently recognised how dangerous the Russian regime’s lobbying efforts in Brussels have been and proposed to ban Russian companies from hiring EU lobbying and public relations firms which, according to EU Observer, make 3.5 million euros a year from such deals. While this is a positive development and a necessary step, the proposal has not yet been approved by EU member states.

The EU has already paid 57 billion euros to Russia for fossil fuels since the war started.

The EU: Climate leader or climate laggard?

With the UK failing to meet its climate targets and aiming to scrap the law protecting its most important wildlife sites, the recent US Supreme Court decision limiting the Environmental Protection Agency’s capacity to restrict CO2 emissions – effectively delaying any meaningful climate action by the US, and the energy crisis raging across the globe, climate politics needs a leader more than ever. While the European Commission has been saying all the right things about the need to tackle the climate crisis and playing a decisive role in the new climate order, the taxonomy proposal tells a different story.

Just a little over a month after announcing its plans to speed up the energy transition and secure energy independence from Russia through RepowerEU, the approval of the delegated act not only strengthens Putin’s geopolitical influence in the region but also sends mixed messages about how seriously the EU takes the climate crisis. Therefore, in addition to exposing the deep rifts between the EU member states when it comes to how to tackle the climate crisis, the EU Taxonomy also risks hindering the credibility of the entire EU climate agenda, the European Green Deal, and the EU as a climate leader. In a world where even Russia and China do not include gas in their respective taxonomies on sustainable activities, the EU’s labelling of nuclear power and fossil gas as green energy resources sets a dangerous precedent and it is a clear sign of a failed climate leadership.

Where do we go from here?

After such a disappointing and greenwashed outcome that discounts the mounting crises we are facing today, the road ahead is blurry and full of challenges. The next step is for the Council of the EU to vote on the proposal, an actor which does have the power to veto the Parliament’s decision. But, as the inclusion of fossil gas and nuclear power was essentially a solution suggested by the member states that make up the Council, and considering most EU governments are in favour, it is safe to assume that the super-majority required for a veto will not be found. With this approval, the delegated act will be expected to come into force from the beginning of 2023.

However, there is still hope, and it lies in legal action. Following the European Parliament’s decision, many NGOs signalled that they were considering or planning legal action. Greenpeace has announced that it will, first, submit a formal request for internal review to the Commission, and if the result is negative, it will pursue legal action at the European Court of Justice against the Commission for including fossil gas and nuclear energy in the taxonomy. Moreover, Luxembourg and Austria will also join Greenpeace in challenging the Commission through the same court. Spain and Denmark announced that they would also consider joining the lawsuit.

In recent years, citizens have been taking their governments to court to hold them accountable for failing to take sufficient measures to meet their own climate commitments. The promising success of ground-breaking cases such as the State of the Netherlands v Urgenda Foundation and Notre Affaire à Tous and Others v France showed how climate litigation can be an instrument to fight climate injustice and a powerful tool to tackle dirty politics or slow political progress, as well as paving the way for further lawsuits.

As more and more courts find a link between environmental harm and the right to life and a coalition of resistance grows against the greenwashed EU Taxonomy Regulation, one question remains: could legal challenges to the EU’s Climate Law lead to similar outcomes and victories for climate justice?