Time is an extremely unequal resource in society. It is urgent and necessary to recognise the right to time for a more balanced use of time, for greater equality, and for human wellbeing and sustainability. Progressive time policies are a well of untapped benefits for society, which we must explore and implement now. Spain is leading the way.

“Sorry, I just don’t have the time.” When it comes to the things that really matter in our lives, we say this all too often. It is becoming clear that our current time management model, designed in the 19th century, no longer reflects our needs. We long for a new way of organising our time that allows us to achieve a better balance between paid and unpaid work, caring for others and for ourselves, enjoying free time, participating in civic and democratic life, and resting.

Our latest issue – Aligning Stars: Routes to a Different Europe – is out now!

Read it online or get your copy delivered straight to your door.

An outdated time management model

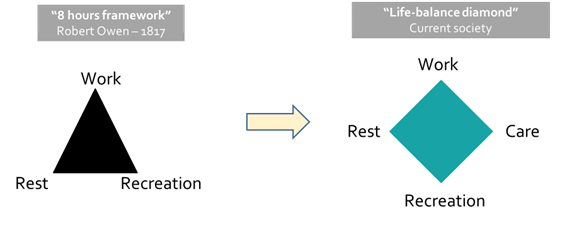

In 1817, Welsh utopian socialist Robert Owen, catalysing demands from the incipient labour movement in the early years of industrialisation, proposed an eight-hour working day to combat the 10 to 16 hours that had become the norm in large factories. This developed into a slogan often heard at workers’ demonstrations in the late 19th century, “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will!”

The introduction of a universal eight-hour working day in many Western countries after the First World War – the first of which was Spain – was a clear victory for the labour movement. A century later, however, this model has become outdated. In not taking caring time, among other aspects, into consideration, it fails to respond to current social needs. The effects of this time management dysfunction include poorer health outcomes, inclusion deficits, and reduced social and corporate efficiency — not to speak of issues with democracy and sustainability.

Time management – the key to a more egalitarian society in the 21st century

In 1990, roughly seventy years after the first moves to legislate for time management in the workplace, the women of the Italian Communist Party made a first attempt to develop a more comprehensive “time law”. It included a proposal to revalue the economy, centred around the processes involved in sustaining human life. In 2000, Italy approved the “Turco Act” on parental leave and urban time regulation, which included a number of these proposals.

At a European level, a Working Time Organisation Directive was introduced in 2003, followed by the Work-Life Balance Directive in 2019. Four years later, time management is back on the agenda again in certain European countries, with four-day working week proposals in Germany and the UK. However, reducing the issue to paid work alone fails to give us the full picture. Although gender equality in the EU has increased in recent decades, the pace of progress has been slow, and gender imbalances are still evident in unpaid work at home.

In Europe, almost 20 per cent of citizens (rising to 34 per cent of women with children) experience time poverty — meaning that, after doing all of the activities necessary for life (sleep, work, and care), they do not have time for themselves (Vega Rapún et al., 2021). Time poverty is a particular problem among working-class people and women.

A century later, the eight-hour model has become outdated. In not taking caring time, among other aspects, into consideration, it fails to respond to current social needs.

Beyond the specific problem of time poverty, most of us crave more free time and aim to achieve a balance that allows us to live better and with more autonomy over how we spend our time. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was partly this dissatisfaction with contemporary time management that caused Millennials and Generation Z to think differently about their careers and work conditions. In the United States, swarms of Americans have resigned from their jobs since early 2021 in a trend known as “the Great Resignation”. According to a 2022 study by the Pew Research Centre, many are only accepting jobs that allow them more flexibility and a better work-life balance. Across the globe, many workers —especially the younger and better trained— are saying no to working endless hours, having difficulties disconnecting from work, and work-life conflicts.

Another disadvantage of our time culture is that it allows neither proper sleep nor proper rest. This greatly affects our physical and mental health. Thanks to the work of the 2017 winners of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, we now know that living out of sync with our circadian rhythms alters our mood and can increase our risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative conditions. If we want to enjoy better health, our time management model needs to change, especially when defining resting and work or school times. This is particularly important for teenagers, who need more sleep than younger children and adults but often fail to get enough because of secondary school start times. Politicians must understand and promote the importance of sleeping and resting; for our personal health and wellbeing, our social relationships, and our societies – but also for our economies. Productivity losses and an increased risk of mortality related to sleep deprivation cost developed economies billions of euros per year. As indicated by the World Economic Forum in 2019, the countries that sleep more have a higher GDP.

We urgently need to make the shift away from Robert Owen’s eight-hour framework and find a new approach that can democratise the way we use our time, both socially and individually. Time is a political issue and must be conceptualised as a right for all citizens. In order to tackle it, we will need to use transversal public policies devoted to improving the way time is currently set. The Barcelona Time Use Initiative for a Healthy Society (BTUI), a global initiative promoting time policies and the “right to time”, recommends that such policies be based on a “life balance diamond”, in which the three pillars of the eight-hour framework are joined by a fourth: care.

Time policies to foster more sustainable, resilient, and democratic societies

From steady-state economics to degrowth, from wellbeing to ecological economics, a growing field of new economic thinking aims to free our societies from the absurd paradigm of infinite growth. The inclusion of time in economic calculations – in a similar way to ecological impact and other key parameters – will becoming increasingly important in the future. Time policies can make a vital practical contribution to the doughnut economics model by helping to set its social foundation while ensuring that we remain within planetary and social boundaries.

Working time is one of the most recognisable aspects of time management. As underlined by the International Labour Organization’s 2019 Guide to developing balanced working time arrangements, “decent working time” is an essential component of “decent work”. The evidence demonstrates that more balanced working time promotes individual and business efficiency — and, at the same time, increases worker satisfaction levels. A society that grants the right to time works better and helps create the conditions for talent development and innovation.

The definition of working time needs to be adapted to the 21st century context, defining a new balance between working, resting, care, and recreation time. Politicians, unions, and companies’ organisations must promote a more flexible, autonomous, and democratic approach to working time organisation.

While maintaining a focus on working time, time policies must also embrace the bigger picture. A new, global approach to time management is directly linked to a commitment to proximity policies, sustainability, and digitalisation – embodied in the 15-minute city concept, support for teleworking, and the decentralisation of co-working, as well as reductions in working days and/or hours. Such an approach – as demonstrated by cities such as Rennes, Barcelona, and Milan – saves on unnecessary travel and, in doing so, reduces CO2 emissions, strengthens communities, and gives individuals greater autonomy over their time. A further proposal is to dismantle the neoliberal idea that all services must be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This would also make a significant contribution to energy savings, especially in small and medium enterprises and in the industrial sector.

If we want to improve the quality of our democracies by increasing civic involvement, we need to democratise access to free time. If a society does not have enough free time, it is impossible for its members to take part in communal and democratic life on a sustained basis. As underlined by a recent opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee, lack of time has a direct effect on civic involvement by citizens and civil society organisations. Those people experiencing time poverty, especially working-class people, face particularly tough barriers to engaging in civic participation.

If we want to improve the quality of our democracies by increasing civic involvement, we need to democratise access to free time.

A new approach to time management will also affect how our society understands human relationships. At present, these are increasingly transactional: monetised and timed for pure utilitarian effectiveness. Time policies designed at regaining free time are also a tool to foster human exchange and discussion and are ultimately a tool to rebuild our failing social fabric. So-called “time banks”, in which citizens exchange time (instead of money), are a good collective example of this. In this way, time policies can be a tool for togetherness; a way to fight atomisation in our society.

Right to time policies already becoming a reality

Municipalities and regions are currently the major driving force behind right to time policies. Barcelona, Strasbourg, Milan, Bolzano, and Rennes are known for their time policies and are setting an example for others to follow, especially in Europe and Latin America. But right to time policies must also be introduced at a national level and from a European perspective.

In addition, many countries, regions, and companies are experimenting with a four-day week approach. While this debate is to be welcomed, progressives and transformatives must go beyond these initiatives to promote a new, wide-ranging framework based on the right to time as a universal 21st-century right, as agreed by the signatory organisations of the Barcelona Declaration on Time Policies.

In order to guarantee all citizens a right to time that gives value to rest, care, and civic time and aims to end the unequal distribution of time in society, the “life balance diamond” must be mainstreamed in both public and private policies. Examples of care-related policies include free, public childcare (from birth to three years) and high-quality, affordable nursing and residential homes for the elderly. Policies to facilitate the reconciliation of work and family life may include the introduction of equal, untransferable, and fully paid leave for both parents in the event of the birth or adoption of a child; the elimination of maternity discrimination and gender inequality in relation to caring responsibilities; and the creation of a family-friendly work culture. Policies on the implementation of permanent time zones, the definition of new social and labour time frameworks, and the modification of school starting times – to name just a few – should be evidence-based and support the right to time.

In this regard, there is encouraging news from Spain. The left-wing Sánchez government has expressed its willingness to approve a law on time use that ensures the right to time, expected in April 2023. Efforts are being led by Minister of Labour and Social Economy Yolanda Díaz, who is known for her capacity to reach agreements with unions and business organisations. More than one hundred years ago, Spain was the first European state to legislate a 40-hour working week in all sectors. Now it may well become the first country in the world to introduce a law on time use. It’s about time.