On one Mediterranean island, the words resilience, autonomy, and solidarity are much more immediate and concrete than EU jargon would lead us to believe. In a process started amid the pandemic and now all the more valuable in the context of the energy crisis, the island’s residents have come together to form a renewable energy community. Their story is a reminder that the most secure energy system is distributed, decentralised, and democratic.

A ferry leaving the island of Ventotene for Formia is noticeably busier than the one heading in the opposite direction. Islanders doze while tourists snap one last photo of this small Italian island’s colourful houses as it slowly recedes into the distance. Summer is over and with it the tourist season. The island is emptying – not just of tourists but inhabitants too. Of some 800 residents, no more than 200 remain.

“In winter, this bar is one of the few places where young people can meet. Staying open is a choice, but it’s a choice that carries costs,” says Antonio Psaros (Toni to friends) as he turns off fridges, worried about running costs. He adds: “Last year, my electricity bill for July and August was 800 euros; this year it was 1500 euros. For small businesses like ours, the increase hits hard.” Psaros has decided not to close after the summer to give people who chose to remain on the island somewhere to go. It is a choice made for himself and his com- munity, one that has led him to rethink his role on the island and also to join the Ventotene renewable energy community. “As well as the environmental benefits, being part of the renewable energy community can help get us through these tough times of rising gas and electricity prices,” says Psaros, as he searches on his phone for his most recent bill to demonstrate his point.

There are 38 officially recognised renewable energy communities in Italy and another 65 are planned, according to Legambiente, Italy’s leading environmental campaign group. Renewable energy communities are driven by the need to create new ways of producing, distributing, and consuming energy based on sharing and saving. Energy is generated by local systems and shared by consumers located nearby. Community members are not just “consumers” but “prosumers” who also own the energy production systems, which in turn become sources of economic, social, and environmental value for the local area.

Renewable energy communities are regulated at the European level by the Renewable Energy Directive, which sets out the EU’s targets for decarbonisation and the rollout of renewable energy sources for 2030. The legislation saw a first partial transposition into Italian law in 2020. In 2021, the directive was fully transposed and it became formally possible to create renewable energy communities in Italy. Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan, funded by the EU pandemic recovery fund, allocates some 23.8 billion euros to renewable energy and 2.2 billion to renewable energy communities in particular.

Renewable energy communities are driven by the need to create new ways of producing, distributing and consuming energy.

“Legally recognising renewable energy communities is an important step for Italy, because it means supporting this type of energy production. It’s an ideal model because it’s based on local, renewable sources as opposed to the current model that is centralised and dependent on fossil fuels,” explains Tommaso Polci from Legambiente’s energy office. Polci adds: “Renewable energy communities bring a human side to a world that can seem distant from us. When we turn on a light, we don’t often wonder where the electricity comes from. Renewable energy communities lead us to ask ourselves where the energy we use is generated and to understand its value.”

On the same street as Antonio Psaros’s bar, a green sign outside a café run by Alessio Castagna reads: “After the summer, the historic Art Cafè will become a workshop for facilitating and supporting circular economy and regeneration projects to protect the island’s environment and culture.” Castagna joined the renewable energy community straight away. He opens the doors facing the bar’s terrace and points upwards. The sun is blinding; it is hard to see what he is pointing at. “The panels will probably go there,” he says.

“Dream in progress,” says the sign at the entrance; a dream that Castagna would like to share. In the Fascist era, political prisoners were confined to the island. “In the days of internal exile [during the Fascist regime], this was the socialist canteen; today, I see it as a place to listen, dream, and make plans together.” This is how Castagna sees participation in the community: “When you aim for self-sufficiency, you need to think long term. A community decides together that the place from which it earns a living is also a place to conserve. And that place becomes home to the group of people that look after it.”

For many years, Castagna travelled the world as a photographer and documentary maker, leaving somebody else to run the bar. Then, unexpectedly, Ventotene became home once more. “In the past, I would only do the tourist seasons and then I would leave, like everybody else.” In 2020, Castagna spent a few months – not just over the summer – on the island. He explains: “Being here with all the problems – the pandemic, the restrictions – a support network began to form. There was a period of shortages on the island, so everyone started working together. At that moment, when we all found ourselves a bit stuck, I started to see opportunities for believing in new ideas and possibilities.”

The idea for a renewable energy community began to take shape amid the restrictions and lockdowns thanks to Gabriele Magni, now a PhD student, who was finishing his degree in energy engineering during the pandemic. With childhood ties to the island, he would often come to Ventotene for the summer season. Then, says Magni, “I began going there more and more, then Covid came. In Rome, I was just uncomfortable and useless. I had a place I could use in Ventotene and I decided to spend the winter on the island for the first time and write my master’s dissertation. Being in close contact with the island gave me the idea of writing my dissertation about Ventotene.” Working with his supervisor Professor Andrea Micangeli, who teaches energy systems at Rome’s Sapienza university, Magni analysed potential models for a renewable energy community on the island. His knowledge of the island and its inhabitants gave him a head start. He began knocking on doors, explaining what he was doing, asking people what they thought about his idea, and seeing if they wanted to be part of the community. It was an exploratory survey that immediately brought Magni into contact with the island’s government: “The mayor openly welcomed the idea and passed a local council resolution declaring his intention to create an energy community. In October 2021, Ventotene’s community energy association was officially set up.” This organisation gave the green light for what had initially been no more than an academic paper.

Renewable energy communities lead us to ask ourselves where the energy we use is generated and to understand its value.

When the council entered special measures (meaning the new renewable energy community had no president, as this role is also fulfilled by the mayor), the establishment of the community was partially interrupted. But relationships continued to be built during this enforced pause. Helping Gabriele Magni was Gloria Consoli, coordinator for the Ventotene community cooperative. Magni outlines the various stages involved: “We started putting together a mailing list of interested people to whom we sent information about what a renewable energy community might look like and how it works; we held several meetings throughout the year where we explained what it is, how it might be done and the next steps for moving forward.” Consoli’s approach involved “thinking about the renewable energy community as a community in the true sense of the word. We organised fundraising dinners so that we had a nest egg by the end of the year to reinvest in other activities.”

Consoli also promotes working groups comprising Ventotene residents of all ages. They usually work in teams, for instance when workshops are offered. Recalling one activity, Magni explains: “We analysed the pro and cons of setting up a community: we didn’t just get people to give presentations we started a participatory process that resulted in the drafting of an energy transition agenda for the island of Ventotene.” Consoli goes on to add that while community spirit is fundamental, it is not enough on its own: “A lot of work needs to be done on governance – in other words, the financial side of things – to understand what projects can be implemented with the money that is generated.” The watchwords are education and awareness. Each person, based on their background and needs, uses their know-how in different ways.

“Our hotel is only open in the summer. So we see our participation as an exchange: in winter, when we’re not working, we can help keep costs down for individuals or small businesses through the energy that we produce, while they help us during the summer,” explains Nicola Assenso, who runs the Hotel Calabattaglia. He has lots of space to install solar panels, but the electricity produced would go to waste when the hotel is closed: “We can create quite a big system and therefore also supply energy to people who cannot install panels.” Assenso embraces a redistributive idea of energy that is especially relevant when many families are struggling with rising prices and the energy crisis. “This is a small island. If everyone were to join, it would be possible to completely abandon fossil fuels, thus becoming a shining example in the European Union.”

Antonio Psaros is also positive about the community’s future: “The more people that are involved, the more others will want to get involved,” he says as a friend walks in. He sits down and they begin chatting. About the friend who is leaving this year. About rising coffee prices. About too much wine the other night. About how much energy ovens use. People’s everyday lives are scarred by the climate crisis, energy crisis, political crisis, and economic crisis; crises that become intertwined with and shape social relationships. What might seem like a small local experiment is, in fact, a laboratory for innovation and ideas. The tiny island of Ventotene, the first renewable energy community in the Lazio region, can blaze a trail and – together with other municipalities – build a chain of energy communities across the country.

What might seem as a small local experiment is, in fact, a laboratory for innovation and ideas.

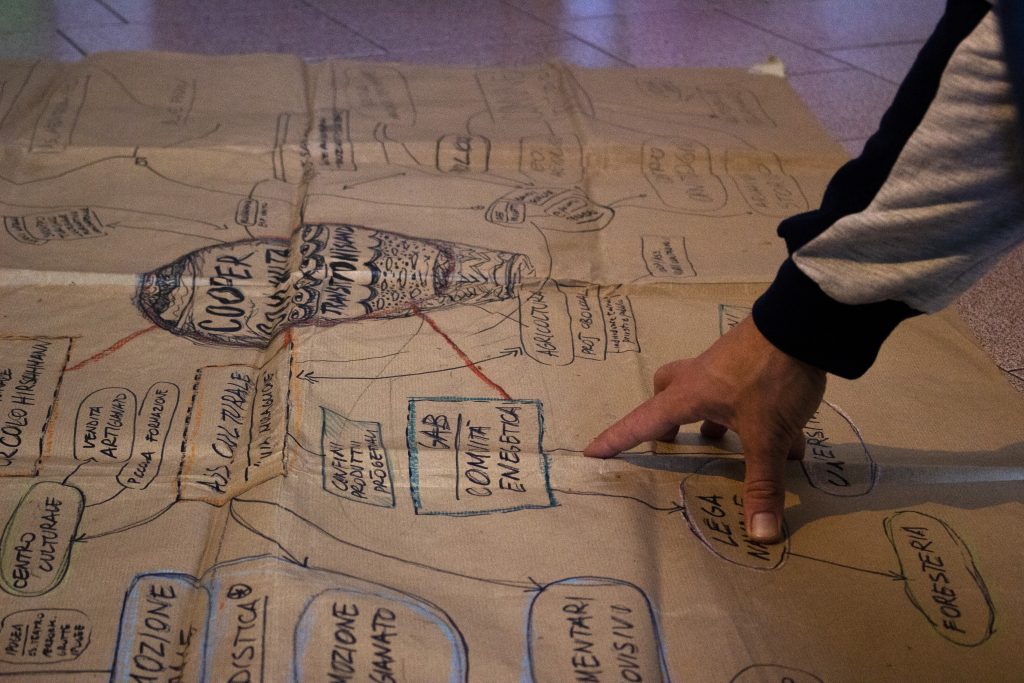

Alessio Castagna takes a large sheet of paper out of a drawer. As he does, he tells us about his non-profit Sconfinata, which promotes social inclusion and training initiatives all year round and also collaborates with and shares the same values as the renewable energy community. Alessio opens out the sheet. Arrows pointing up and down represent the relationships between organisations and people on the island. It is a sort of organisational chart, with a box containing the words “energy community” in capitals and lots of other names connected to it: “Gabriele Magni”, “University”, “Sconfinata”, and more. An arrow points to Lega Navale, a national sailing charity. “We were among the earliest supporters,” says Francesca Rizzi, vice-president of Ventotene’s Lega Navale chapter. On the island, the Lega Navale is known for its environmental work and for championing a sustainable relationship with their surroundings. “Since 1997, when the protected marine area was created in Ventotene, we’ve always believed that what we have beneath our feet must be preserved.” Naturally, they embraced the community, well aware of the importance of pooling knowledge, making shared plans, and finding solutions. These are the same ideas that the Lega Navale teaches at its sailing school: “Coordination, relationships, and a sense of community play a key role both at sea and in the renewable energy community. We’re all in the same boat.”

The climate emergency, the energy crisis, and inflation are challenges to be faced as a collective. The sharp increase in energy and food prices has been keenly felt in Italy due to its dependence on imports. The geopolitical instability caused by the conflict in Ukraine and the effects of the climate crisis, such as Europe’s drought, hit the poorest hardest, increasing inequalities. So it is becoming more urgent than ever to embark on an energy transition based on the fair and sustainable sharing of resources. “Renewable energy communities are a useful tool against fuel poverty,” says Tommaso Polci, reflecting on the experience of a renewable energy community that was created in deprived areas of Teduccio and San Giovanni in Naples. “As well as saving families money, it’s an opportunity to reshape communities. These neighbourhoods were infamous for crime, but for once they are talked about differently.”

Economic, social, and environmental dimensions are blended into a common approach based on reciprocity and exchange between the community and the local area as a whole. “The energy community should also act as means for redistributing disposable income and energy, as a means for equality. It could help close the gap between social classes, which has been widening in recent decades,” explains Raffaele Spadano, an anthropologist who manages the Gagliano Aterno Community in the Abruzzo region. He adds: “People say there’s no alternative, that we can’t do anything to stop climate change, the pandemic, war. But renewable energy communities allow us to start afresh by going back to basics. The value generated from nature (water, wind, sun, biomass) should stay with the residents of those areas; at the same time, we need to ensure that system management and maintenance is outsourced locally.” Gagliano Aterno is a small village in the Abruzzo mountains, and Spadano sees energy communities as an important means of restoring a sense of community, something increasingly threatened by depopulation. “Setting up a community takes time, years even, and over these years the community needs to be supported. Very often we’re faced with situations where communities have frayed, deteriorated when it comes to relationships, so the first thing they have to do is rediscover the collective dimension.”

There remain many obstacles to the development of renewable energy communities in Italy. At the European level, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands all have far more officially recognised renewable energy communities. That said, in recent years Italy has seen many initiatives that may not be included under the renewable energy community legal framework but have nonetheless promoted self-production and local renewable energy sources. “In 2021, Italy was some way ahead of some European countries but with these delays, we’re wasting time and fall- ing behind,” laments Polci. Delays due partly to legislative instability as well as hold-ups with technical regulations, which have prevented the installation of new panels, including on Ventotene. Legambiente points to the serious delay in the guidelines for self-production that should be issued to Italy’s energy regulator as part of the transposi- tion of European directives into Italian law. There is a lack of clarity on updates to incentive mechanisms, which are essential for starting many communities in Italy, as well as other technical issues. As Polci explains: “Members of an energy community must all be connected to the same primary substation. To find out which substation you’re connected to, you have to contact your local energy supplier (usually Enel). This information is needed to take the first step, but there’s often a very long wait for it.”

As Gloria Consoli explains, setting up the Ventotene renewable energy community was an uphill battle too. As well as delays due to compliance and the council being in special measures, there were also problems connecting to the grid, which forced the community to start with only a few members. A 2022 report into energy communities in Italy highlights that, when it comes to European energy transition targets for 2030, the country “is lagging behind, so much so that on 26 July 2022 the European Commission opened 10 infringement procedures for [Italy’s] failure to implement several directives, including the directive on energy communities.”

Establishing more energy communities would bring nationwide benefits, creating positive dynamics that would allow people and businesses to invest independently in their local areas and avoid the delays and political obstacles that all too often hold up the energy transition. Magni concludes: “The next step will be to create networks of energy communities to share good practice. But first, we need to set them up.”