Progressives have historically found strong support in cities. With countries turning to the right and cities like Berlin falling out of progressive hands, progressive forces at the city-level are understandably nervous. Ahead of the Spanish local elections this month, Filipe Henrique asks if this trend could soon sweep across cities and how progressives can maintain their influence in cities.

For centuries, cities have served as progressive harbours. Cities are places where different cultures meet and marginalised communities can find refuge. Cities are where progress starts, and in Europe, they are where most people live.

In 2015, a progressive and Green wave swept across cities such as Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia. In 2019, progressives lost Madrid. Wider progressive gains are once again at risk as Spain returns to the local election polls at the end of May. Progressives are understandably grappling with questions: could Spanish cities suffer the same fate as Madrid or even Berlin and Lisbon? Are cities across Europe also in a seemingly unstoppable turn to the right?

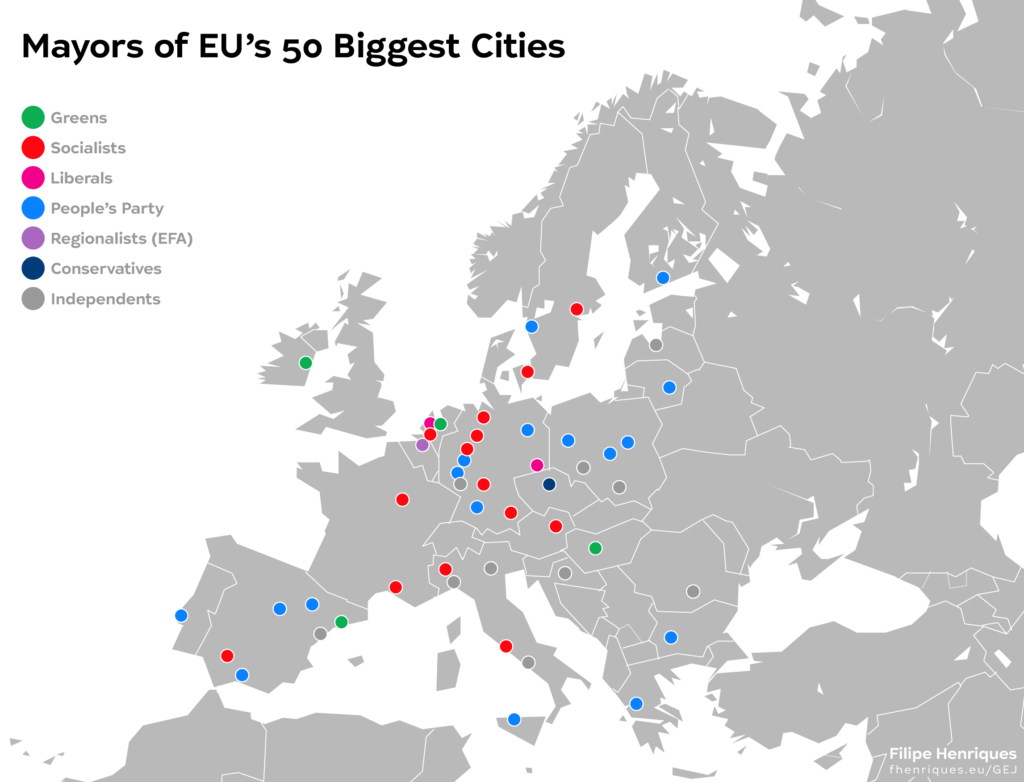

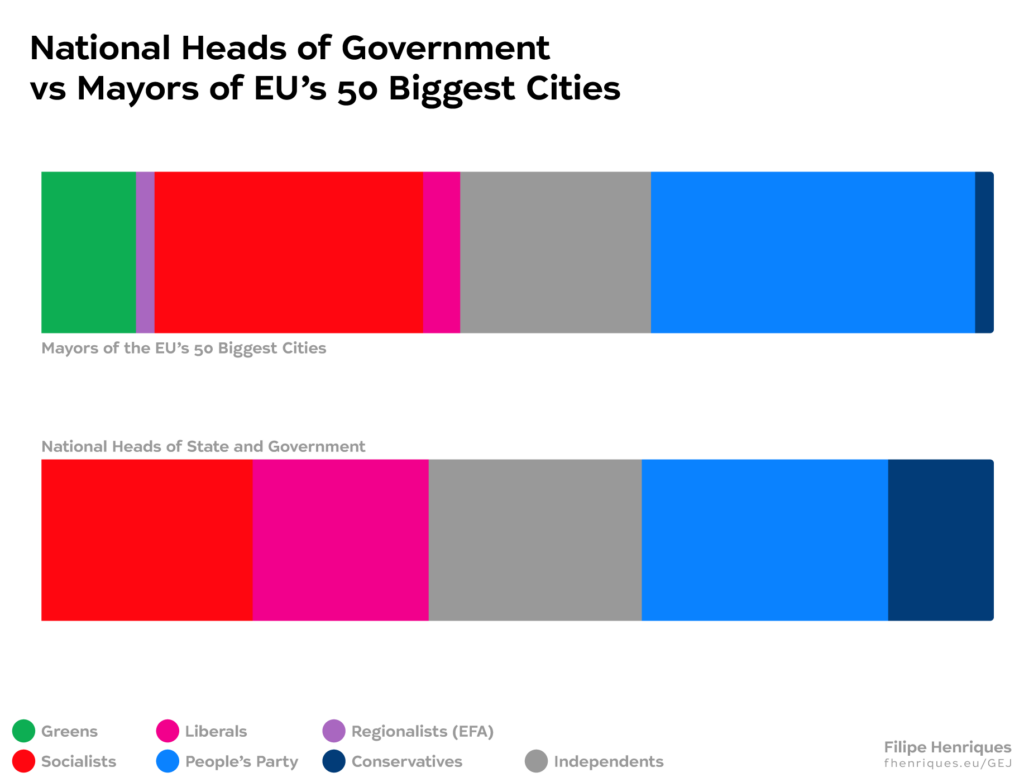

For now, examining the EU’s 50 most populous cities as well as the political landscape at both continental and national levels reveals a stronger representation of progressive forces in governments compared to the radical right.

However, there are some exceptions to this trend in European cities. For example, Madrid and Antwerp have right-wing mayors who have led efforts to radicalise debates in their own countries. Madrid itself has a strong right-wing history, having been continuously led by the Right since the early 1990s with the exception of the four years when Manuela Carmena led a Left-Green 1-seat majority. Others like Helsinki or Athens are traditionally right-wing strongholds.

Still, cities across Europe lead progress. Budapest Mayor Karácsony (from Párbeszéd, a soon-to-be member of the European Greens) and Zagreb Mayor Tomašević (from the Left-Green Možemo) lead progressive capitals in deeply conservative countries. Not only have they recovered their capital cities from corrupt populists, but they have also offered new models of progressive politics which can still be transported to the national level. The same is true for cities such as Riga or Milan, where independent mayors closely aligned with the Greens have defended LGBT people against attacks from their national government.

In countries like Poland where the rule of law is under threat, and where the pro/anti-democracy debate prevails over the left-right divide, progressives are growing in strength in cities. Warsaw’s Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski is the clearest example of this. In Czechia, the mayor of Prague is the only big city mayor of the European Conservatives, but he’s also in a coalition of the progressive camp.

Barcelona and Valencia – both governed by alliances of Greens, Left and regionalists, and Mayors Colau and Ribó respectively – were examples for the national government that emerged in 2018. Progressive governance has inspired a policy shift away from cars to lighter modes of transportation as well as greater focus on tackling the housing crisis that overtouristification of cities has created. Despite this impact, it has failed to maintain popular support.

While the 2015 elections gave momentum to a new progressive and Green movement, the 2023 elections might have the opposite effect. The divisions within the progressive space, and the abrasion of power might all provoke a domino effect in the December national elections which could see the far-right return to the Spanish government for the first time since the 1975 transition. Such a turn would effectively end one of the few progressive governments in the European Union and undermine European governance.

The fortunes of progressives in other cities like Berlin and Lisbon should trigger alarm bells. Both had been examples of center-left leadership supported by a broad majority that included Greens and leftists. This represented new models of majority government, which in the German case has not yet been seen at the national level, while in Lisbon was part of the base of the 2015 government. However, division within the progressive camp spelled their eventual loss to conservatives. In the case of Berlin, conservatives have taken power with full support from the Socialists, which once again preferred to be subordinate to the Conservatives than to lead a progressive alliance.

Cities have been, and will continue to be, the centre of progressivism. It’s in cities that progressives can win majorities and directly demonstrate the positive impact of their policies to citizens. Across Southern and Eastern European cities, progressives in power have shown a new model of governance that could be replicated at the national level.

Yet cities are not progressive strongholds that we can take for granted. Progressives must strengthen participative democracy by co-creating change with those who live in their cities. The organised backlash to key measures for the good of the social majority, like the Good Move project in Brussels or the pedestrianisation of roads in Barcelona by Superblocks, is something that progressives will always have to be ready for. At the same time, they need to rebuild alliances with those that can make a social majority stronger, and not allow their strongholds to turn conservative as seen in Berlin or Lisbon.

The kind of cities we build determines the society we become. The capacity of progressives to win power and transform our cities is what can create the momentum for us to change our countries and continent. What happens in cities like Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia therefore matters for the 2024 European elections.