Across Europe, political landscapes are breaking apart as once dominant parties splinter and lose support. In national elections this January, the Portuguese Socialist Party defied the trend to win an absolute majority. The victory seemingly confirmed Portugal’s status as a political outlier in Europe. But a closer look at the results reveals change bubbling under the surface and likely instability to come.

Over recent years, the two largest political families in Europe – the Socialists and the Christian Democrats – have been losing ground as party systems have fragmented. This was a trend that materialised in elections in 2021 in the Netherlands, Cyprus, Czechia, and Bulgaria. Even in Germany, where the Social Democrats came first to claim the chancellorship, the party failed to improve on their 2017 performance. Meanwhile, the Christian Democrats recorded their worst ever result.

It was therefore surprising that the Portuguese Socialists achieved their best-ever results in January’s general elections. Despite leading the government for the past six years, the Socialists managed to secure an absolute majority and will no longer have to rely on external support. However, a result that could appear to mark the end of the trend towards electoral fragmentation may actually represent its continuation.

The shifting landscape of the Portuguese Right

Since the beginning of its democracy, Portugal has had two prominent right-wing parties. The largest is the Partido Social Democrata (Social Democratic Party, PSD). Named after the German centre-left SPD, the party’s seemingly left-wing origin is explained by Portugal’s left-wing revolution that took down a 50-year-old right-wing dictatorship in 1974 and coloured the entire political spectrum. The party applied to join the Socialist International in 1975, only to be vetoed. After gaining seats in the European Parliament for the first time in 1987, they joined the Liberal Group where they remained until 1996, when they joined the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP). The other – CDS-Partido Popular (People’s Party, CDS-PP) – was a conventional European centre-right party until it was expelled from the EPP in 1993 owing to its resistance to the Maastricht Treaty. It then joined the precursor to the present European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) in the European Parliament, only returning to the Christian-Democratic family in the 2000s.

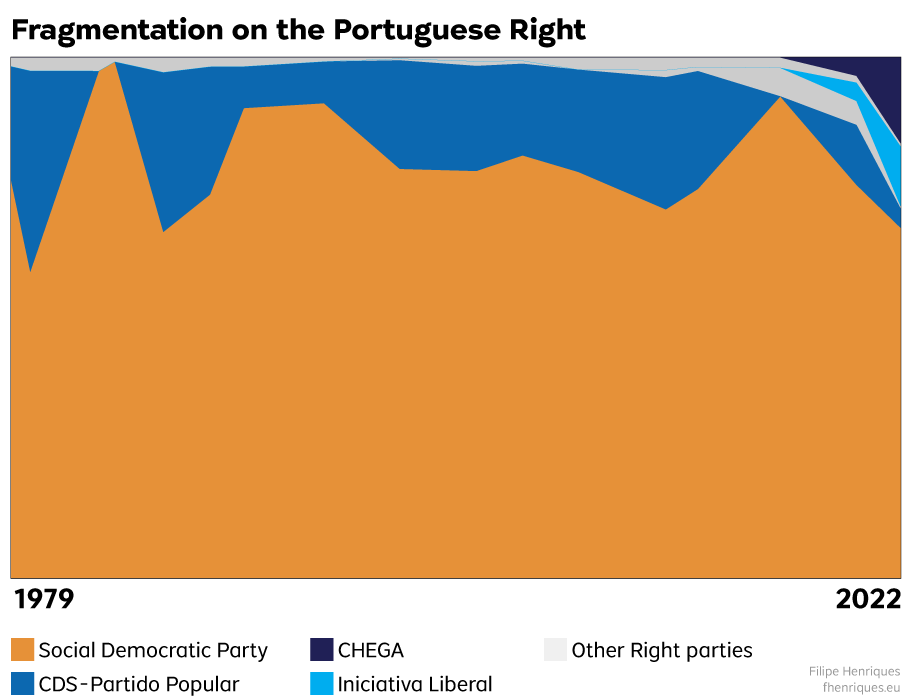

So while these two parties – PSD and CDS-PP – are now counted among the ranks of the EPP, their political affiliation and ideological positions with the Right have shifted and evolved over time. This evolution has allowed them to cover the entire right-wing space and generally win well over 90 per cent of right-wing votes.

But the rise of the liberal Iniciativa Liberal (Libertal Initiative) and the far-right Chega demonstrates how the Portuguese right-wing space has now become fragmented in the same way as in other European countries. From two centre-right parties that covered the entire spectrum, Portugal now has three sizeable actors in parliament: one centre-right, one liberal, and one far-right party.

The far right in retreat?

Behind the headline left-wing victory, the reality is that right-wing parties gained support at this election. Together, the Right gained 8 percentage points and seven more seats than in 2019. It now represents 43 per cent of the electorate.

Iniciativa Liberal is a right-wing liberal and libertarian party. On economic matters, they call for small government. On social issues such as LGBT rights, reproductive rights and euthanasia, however, the Liberals are the only right-wing force to defend progressive positions. They performed well in urban areas along the Portuguese coast. While their national result did not reach 5 per cent, they easily surpassed that score in Lisbon and Porto to become the third-largest party in Portugal’s main cities.

Chega is a far-right party with a clear rural vote base. Besides its conservatism, xenophobia, and antigypsyism, Chega are supporters of the free market. As such, they are closer to Spain’s VOX (which gained 15 per cent in 2019’s Spanish election) than to most of their counterparts on the European far right. Yet, unlike in Spain, Portugal’s mainstream right-wing parties still maintain some sort of cordon sanitaire around the far right, even if it’s a weak one that can easily fall when power is in sight, as happened in the region of the Azores in 2020.

While Chega’s 7 per cent and almost 400,000 votes is something that should worry every democrat, it is a significant decrease from the 12 per cent its leader, André Ventura, achieved in the Presidential election in early 2021 when he gained almost half a million votes. Their emergence onto the political scene, propelled by the outsized media attention they receive, and the future role of the far right in Portuguese politics will depend on how their parliamentary group behaves and how the mainstream right treats them.

Unity remains a distant prospect on the Left

The resurgence of the Socialists came as something of a surprise. The country entered the last week of the campaign with a sense of stability in instability (I noted in a previous article ahead of the elections that “in any event, Portugal seems headed for another period of political turmoil”). During the week ahead of the vote, there was a real possibility of a right-wing majority. PSD leader Rui Rio, the main challenger, indicated on the final day of the campaign that he was ready to lead such a majority, even if it included far-right MPs.

Portugal is a young democracy. As Rui Tavares, newly elected MP and leader of the green-left party LIVRE, has pointed out, Portugal’s days under dictatorship still outnumber its days as a democracy. Memory of the regime that ruled Portugal from 1926 to 1974 remains fresh in people’s minds. While that has not prevented the re-emergence of a far-right party, it does give social relevance to a cordon sanitaire.

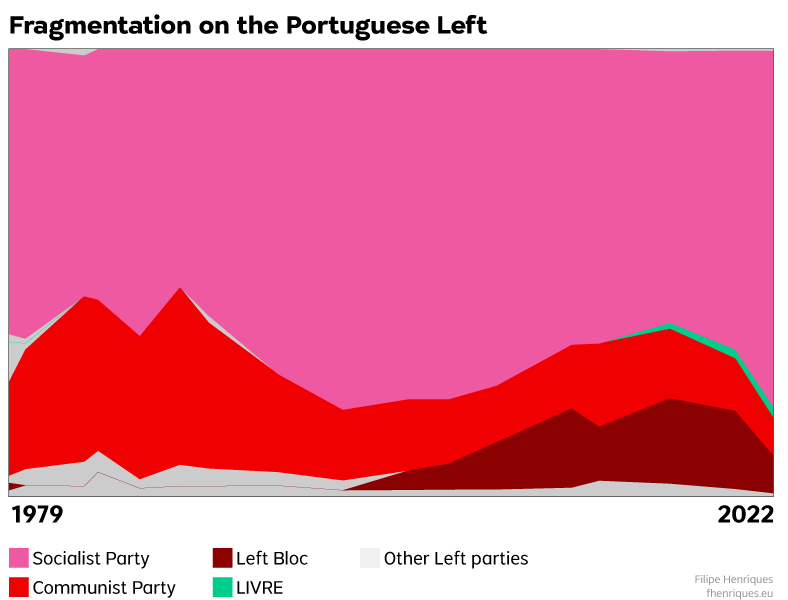

On election day, a wave of tactical voting aimed at keeping the far-right out of government gave the Socialist Party 42 per cent of the vote. The swing cannibalised the votes of the Left Bloc and the Communist Party, both former partners of the Socialists in government. The Left Bloc went from 10 per cent of the vote to 4 per cent, a repetition of what had already happened in 2011 when the Socialist government fell and blamed the parties on its Left for its collapse. The Left Bloc’s electorate overlaps considerably with that of the Socialists, so there is no expectation that their decrease in representation will be permanent.

Meanwhile the Communist Party, which traditionally had a more stable electoral base, has lost almost half of its electorate since 2015. Whether this drop is temporary or signals a deepening of their historical decline since their peak in the early 1980s remains to be seen. Unlike in other countries, the Communist Party has been a strong force for democracy and social rights, and their role in building the Portugal of today cannot be downplayed. Even if their parliamentary strength is weakened, they hold power in cities and towns across southern Portugal and their links with trade unions will be important over the next five years.

Fragmentation of Portugal’s Left is nothing new. During the first decade of democracy, the Socialists never exceeded 60 per cent of the left-wing vote, while the parties to its left generally gathered 20 to 40 per cent of this vote share. Thus, in contrast to the Portuguese Right for which it is a relatively new phenomenon, fragmentation is a long-standing feature for the Left.

While tactical vote may have given the Socialists a strong majority, this cannot be assumed to be a long-term trend. Especially if the Socialists once again fall into the traps of absolute power: arrogance, lack of dialogue, and rejection of criticism. While the Socialists promised to continue the path of social and economic recovery down which they have led Portugal for the past six years, much of that model’s strength came from elsewhere in the parliamentary majority. For example, while the Socialists promised to keep improving the minimum wage ahead of the vote, the proposed rise would still keep the Portuguese minimum wage in 2026 below the current Spanish minimum wage. A one-party majority might mean the continuation of the recovery of the Portuguese economy and social model after the cuts carried out during the 2008 financial crisis, but this recovery will be weaker and less socially conscious.

Portugal’s Green players – seeking strength in numbers?

While in north-western Europe the Greens have emerged as strong players as the traditional party system splinters, this is not the case in southern Europe. Portugal is not different from Spain, Italy, or Greece in this respect. Unlike its Mediterranean counterparts, Portugal has had a stable Green parliamentary group since the 1980s. The Ecologist Party “Os Verdes” (PEV) has been in a permanent coalition with the Communist Party which secured the party two seats at each previous election. While in 2019 its two MPs were at risk, in 2022 they failed to get re-elected and PEV left the parliament.

Portugal’s two other green parties – People, Animals and Nature (PAN) with a centrist outlook and the more libertarian left-leaning LIVRE – will be represented in the next parliament with one MP each. For PAN, which had four MPs in the previous term, this means a step back. Their rhetorical equidistance between the two political blocs made them an easy victim of tactical voting. Yet, they became the first party without roots in the 1970s to enter parliament and remain for three consecutive terms, proving their resilience.

LIVRE, on the other hand, was one of the big winners of the night. After winning a seat at the 2019 election, the party lost its only MP after just a few months, amid great controversy. Heading into this election their chances of gaining a seat were slim to none. Led this time by Rui Tavares, a former Green MEP, they had a stellar performance during the campaign, and performed an astonishing comeback.

The two Green MPs face difficult years ahead. Without a parliamentary group, they will lack resources and speaking time. They will face a one-party Socialist majority and a strong anti-environment right-wing. Since 2015, PAN has managed to force the ruling majority to adopt measures in environmental sustainability, animal protection, and social justice. Now that the Socialists no longer need allies, these might fall. There will be hard battles to fight around Lisbon’s new airport and the development of lithium mining. Overall, the momentum of the transition towards a more sustainable economy will be weakened. While the Portuguese Socialists have greener policies than many of its European counterparts, it was their dialogue with other forces that made Portugal’s path since the financial crisis of 2008 more environmentally and socially sustainable.

Despite their differing political origins and culture, there is striking convergence between LIVRE and PAN in terms of their plans and goals. The Portuguese parliament will now have two Green voices who are independent from third political actors, and their strength and cooperation will be determined by their own will. Only the future will tell whether this marks a watershed moment in the emergence of a strong and independent Green voice in Portugal.