The war in Ukraine and the pandemic have transformed the economic landscape of Europe. Using Eurostat data, Cristina Suárez Vega looks at the demographic factors affecting Europeans’ ability to deal with the fallout.

A series of historic records – that is one way to describe what has happened to the European economy in 2022, though not in a positive sense. In September 2022 inflation in the Eurozone reached 10.9 per cent, its highest rate since 1997. You can now buy far less with one euro than you could in the past. This is nothing new; any product is (almost inevitably) susceptible to upward changes in its price. What has come as a surprise to the European Union is how the cost of living has soared so quickly, jeopardising both the economic health of individuals and societies and the transition to cleaner energy.

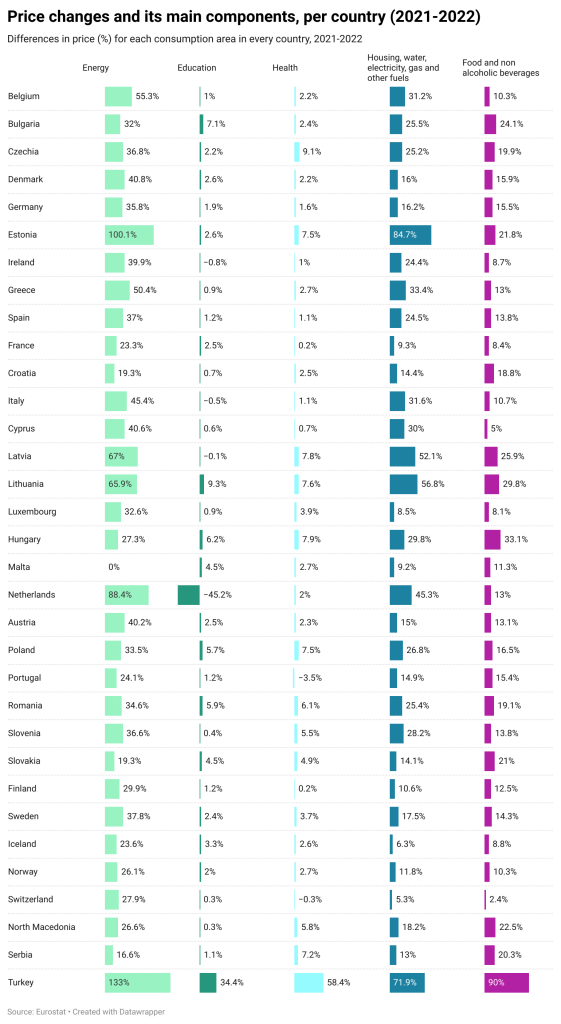

Aside from the pandemic, there is a key factor at play here: the war in Ukraine. Economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU have stopped the importation of gas into Europe, which has indirectly raised the international market price of gas across the continent. As a result, energy prices grew by 37.5 per cent in August 2022. In 2021, by comparison, there was an increase of only 14 per cent for the same month. The difference is even greater if we take a closer look at different EU countries. According to Eurostat, Denmark has the highest electricity prices in the EU followed by Germany, Ireland, and Belgium, whereas Bulgaria and Hungary have the cheapest.

Eurostat has calculated the evolution of consumer prices between 2000 and 2021 to show that, on average, prices rose by 46 per cent. For life’s essentials, the increase was even more pronounced. The cost of energy in 2021 was 111 per cent higher than in 2000. Education has become 95 per cent more expensive. Rent and utility costs rose 72 per cent. The country worst affected was Romania, with a total cost increase of 311 per cent.

We can see a precise turning point: mid-2020, when the pandemic began to take its toll on European economy.

Looking back over the past eight years, prices in the energy sector (crucial for the green transition), together with the cost of housing, have been the most unstable. The same is true for the price of food, although to a lesser degree. Having increased only 2 per cent in 2018, food inflation has surpassed 14 per cent in 2022. If we look closely at the graph above, we can see a precise turning point: mid-2020, when the pandemic began to take its toll on the European economy.

Of course, the pandemic did not have the same effect on all countries. Given the diversity of socio-economic situations in Europe, it is unsurprising that the associated price changes have varied greatly across borders. Energy costs – which rose far more steeply than those in other sectors,[1] aggravated by the war in Ukraine and extreme climate events – increased by 133 per cent in Turkey (although the country’s economic instability has driven prices up past 30 per cent in all sectors), 100 per cent in Estonia, and 88 per cent in the Netherlands between 2021 and 2022.

Young women lose out

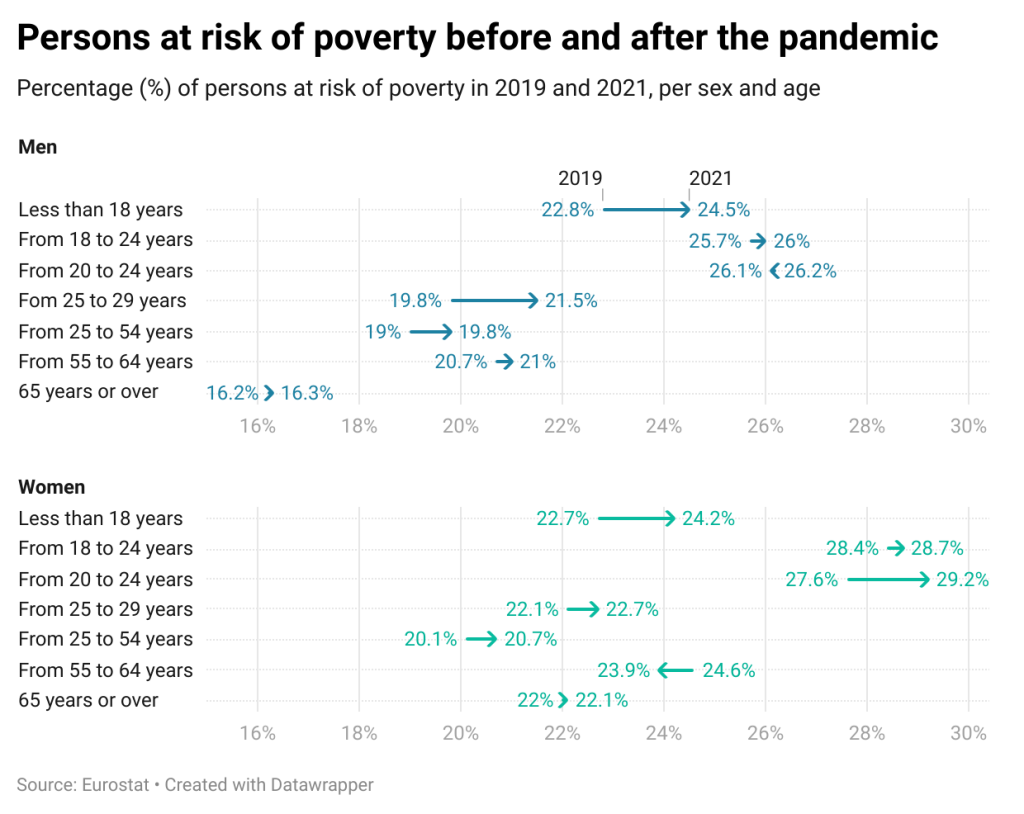

If prices rise and incomes do not follow suit, the result is an increase in poverty levels. But the risk of poverty is not the same across all demographic groups. As demonstrated by the graphs on page 50, poverty in the EU is gendered, and it is women who are most affected. Except for people below the age of 18, the percentage of women at risk of poverty – defined as those whose income falls below the poverty risk threshold, set at 60 per cent of the average national income – is greater than that of men. This was the case before the pandemic, and it still holds today. For men between the ages of 25 and 29, the risk of poverty has grown by more percentage points than for women of the same age, but the actual at-risk percentages for poverty remain higher for women.

The greatest difference between the at-risk rates for poverty for men and women can be seen in the 65-and-over age group. Overall, this age group’s poverty risk increased only slightly between 2019 and 2021. However, the gap between women (22 per cent) and men (16 per cent) stands out as particularly large. The gender pay gap and a greater amount of time dedicated to care work and their effects on pensions entitlements are some of the key factors responsible for this discrepancy.

The percentage of women at risk of poverty is greater than that of men.

In terms of age, the risk of poverty is high- est among young people. The group with the greatest percentage of people at risk of poverty in 2021 was those between the ages of 18 and 29, comprising 33.7 million men and women in total. Responsible factors include poorer working conditions and lower salaries than previous generations, who were able to build a larger financial cushion during previous, more economically robust periods.

Economic fluctuations do not affect all income groups equally; the lower a person’s income, the less able they are to deal with inflation. This means that ultimately it is women and young people – and especially young women, who find themselves at the intersection – who are likely to be most severely affected by the current cost of living crisis.

[1] Except for Malta, which experienced a 0 per cent increase. This may be due to a calculation error.