In Manfredonia, a small town on the Gargano peninsular in the southern Italian region of Puglia, deep scars have been left on the land and its inhabitants by cultural and industrial colonisation. This is a story of democratic exclusion that began with the building of a petrochemical plant on the edge of the town by state-run chemical giant EniChem in the early 1970s. Through a decades-long struggle for health and dignity, a political community was born. Now that the city’s story is being told, democratic movements with a strong environmentalist streak are trying to wrest control of their land from exploitation by organised crime and polluting industries.

In autumn 1988, a rumour spread through Manfredonia’s streets that a ship carrying toxic waste was headed towards the city’s port. It was whispered that the ship was to dump its load into the incinerator of the former Anic EniChem petrochemical plant, two kilometres from the city. The Deep Sea Carrier, which had already been turned away from the Nigerian coast, was laden with 2500 tonnes of toxic materials.

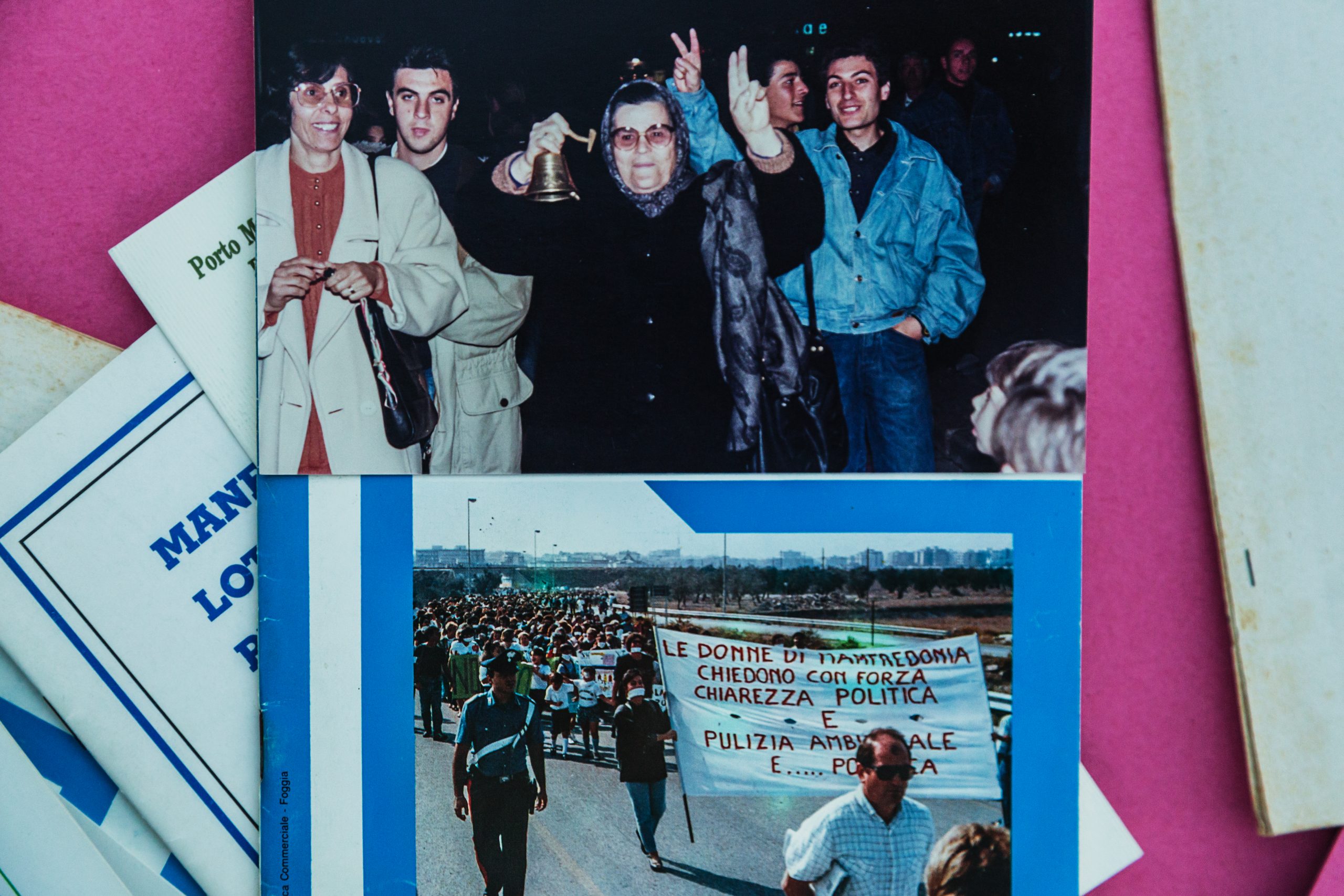

The “poison ship” looming on the horizon provoked a violent revolt among the local population. For four days people protested, taking to the streets and building barricades. Then, out of the disorganised protests, something different emerged. As the ship sailed away from the port, the city witnessed the appearance of street rallies, spaces for sharing, and places where people could find a sense of community and belonging.

Manfredonia’s main square became an agora. Under the steady gaze of the San Lorenzo Maiorano Cathedral, tents were erected and an information hub set up. Between them, the teachers’ tent and the fishermen’s tent began raising awareness of what was happening in the Gulf of Manfredonia. Locals finally lifted the lid on the danger posed by the petrochemical plant, a state-run facility that had operated on the edge of the city since 1971.

Inside the tents, people talked about how the plant’s production processes contaminated land and sea. They found out about the 1976 arsenic leak, long concealed from locals. They recalled the pungent smell of ammonia that, one day in August 1978, had seeped into people’s homes, forcing the whole city to temporarily flee the area.

And so the vivid stories of Manfredonia’s recent history began to make sense within the collective consciousness: they told of a loss of control of their own land, colonial industrialisation imposed from on high, and environmental injustice born from political exclusion.

Bread, tomatoes, and dust

When she was small, Raffaella used to sit on the balcony eating bread and tomatoes: from the seafront apartment building, she could see the Adriatic stretch to the horizon. On the Sunday morning in 1976 when the scrubbing tower exploded and a roar erupted from the EniChem plant, she was 12 years old. As the plume of white smoke and dust split the sky in two, Raffaella abandoned her plate and scrambled inside to get her parents. From parts of the city, a yellowish cloud was seen engulfing the landscape: it stuck to clothes, stained the streets, and coated the shoreline.

Arsenic is an adhesive, odourless powder that does not break down in the environment. It is carcinogenic, even in small doses. That day, at least 10 tonnes of arsenic fell on Manfredonia. After the explosion, the company said that the cloud was just water vapour and asked a team of workers to clean up the area; there are tales of men covered in residue, brushing arsenic off their skin and clothes with their bare hands.

For many, 1976 was year zero. That year, the make-up of the land changed; a spiral of events began that made the area toxic, increasing the cancer mortality rate and the number of birth defects in the local population.1 For 20 years, the plant’s operations led to a series of toxic leaks, including the ammonia release of 1978. Subsequent investigations also revealed that industrial waste was dumped illegally on land and at sea.2

To the residents of Manfredonia, there was no mention of health or environmental risks; the reality was hidden, robbing citizens of their right to make informed decisions.

During the years in which the plant was operational, Michele, the last in a line of fishermen, remembers a strange, stringy alga that appeared on the seabed. Excessive algae is a classic symptom of eutrophication, a sign of damage to an aquatic ecosystem, usually caused by the release of detergents. “I’d never seen anything like it: the algae wasted away in your hands […] when the plant closed in 1994, the algae disappeared.”

Understanding of the plant’s impact on residents’ health and the environment grew slowly, and only in the years following the protests in 1988 and 1989. Too late it was realised that the many cases of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, especially among plant workers, were symptomatic of a larger epidemic of ill health. As local people got sicker and sicker, the fraud that was the petrochemical plant, originally sold to residents as a cure for chronic economic deprivation, became ever clearer.

Economic blackmail

Twelve years separated the 1976 arsenic leak and the 1988 protests. Twelve years in which locals “put up with the plant out of desperation for work”. Manfredonia’s story is also Italy’s story: when the plant opened in 1971, Italy’s economic miracle was still underway, as was its national industrialisation policy. Local people were denied a choice because the industrial plan was presented as the key to post-World War II economic recovery. To the residents of Manfredonia, there was no mention of health or environmental risks; the reality was hidden, robbing citizens of their right to make informed decisions.

“Like many stories of environmental injustice, the arrival of the plant was the result of democratic exclusion. The narrative was that of a big plant coming to a fragile land of misery and migration, and so it was accepted,” explains researcher Giulia Malavasi, who worked on a historical reconstruction of events as part of a 2015 epidemiological investigation conducted by the University of Pisa and commissioned by the municipality of Manfredonia.3 “The petrochemical plant was imposed from on high insofar as no information was provided on its danger. In 1970, there had been a grassroots fight against an oil-fired power station; the discovery that the Gulf of Manfredonia would be full of oil tankers provoked large-scale protests by residents.” But the petrochemical plant was a choice denied: residents did not react to its construction due to a lack of information and the same economic blackmail that would for many years ensure EniChem public forbearance.

When concerns began to spread, it was the late 1980s. At that point, the facility had already altered the area’s socio-economic structure. It fractured the nature of the local economy, moving it away from fishing and farming, and for the first time, Manfredonia saw the birth of a working class. The disconnect between how workers and activists saw the plant created deep divisions within the social fabric. Initially, some workers took part in the protests of 1988-1989, but when the movement called for the plant’s closure, their support fell away. Plant jobs offered a form of security, but in the end, the promised economic miracle never materialised. When the plant closed in 1994, local people were left with no jobs and toxic land.

Institutions under fire

At the age of 25, a young Italian teacher in Sardinia boarded a boat bound for “the Continent” – 1970s Italy. She was leaving the island of her childhood to settle on the Gargano peninsular. Ten years later, Rosa Porcu was one of the many women at the forefront of the 1988-1989 protests that laid the foundations for the grassroots movement to take back control of Manfredonia.

She explains that these years were not just about growing civic awareness, but women’s awakening, too. Through activism, women stepped out of the traditional roles seen in a 1980s southern Italian town. At the time, Rosa was 35 and teaching in secondary schools. She and some of her comrades from the 1988 movement were part of a research collective on women’s freedom and authority. Thanks to this established philosophy, the members of the Donne di Manfredonia (Women of Manfredonia) environmental movement became pioneers in Italian history. Malavasi traces a direct line to more recent women’s movements, such as the protests led by mothers in Campania’s “land of fires” (a vast area between Naples and Caserta plagued by illegal waste fires) and Taranto’s Tamburi district (the neighbourhood that has borne the brunt of dioxin emissions from the Ilva steelworks).

In Manfredonia, Malavasi explains, women became a collective, cross-class political constituency. Rosa remembers women of all ages and social classes taking to the streets, from housewives to teachers. They passed around pieces of paper printed with talking points for starting discussions. Rosa describes it as “a knowledge movement”.

For Malavasi, the environmental struggle of 1988-1989 became a democratic struggle when it started spreading information about the petrochemical plant. With the sharing of knowledge, people became aware of institutional collusion: “The movement was born out of a reaction against a politics of compromise and complete distrust in institutions, so we decided to experiment with ‘another’ politics.”

Malavasi describes the manifold reasons why people in Manfredonia still talk of institutional betrayal today: because the plant was under the jurisdiction of neighbouring municipality Monte Sant’Angelo which, perched on the mountainside almost 17 kilometres away, was never interested in the situation; because, for eight years in the 1980s, EniChem dumped its waste in the sea with ministerial approval; because, in 1989, a parliamentary commission exposed the complete absence of emissions checks by local authorities; and because, after the facility’s closure in 1994, the sale of the concession led to the installation of new highly polluting redevelopments on contaminated areas.

For two years, citizens organised, taking to the streets around the plant en masse. While rabble-rouser Pino, a technician with environmental and social issues at heart, was running around the city handing out reams of flyers and yelling through loudspeakers, the Women of Manfredonia took their protest to parliamentarians in Rome. Armed with 3000 signatures, they also sought justice for the 1976 accident at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Then, one day at five in the morning, the police cleared the tents out of the main square, and the protest began to run out of steam. Even when, reaching its verdict in 1998, the European court found Italy guilty of breaching the right to receive information, the news went almost unnoticed. Today, almost 30 years after the plant closed, the inhabitants of Manfredonia have been left with contaminated land that has yet to be cleaned up. However, the cultural legacy of the protests still lives on among the locals.

The legacy endures

Where the old EniChem plant once stood, today there are only weeds and the white outlines of its foundations. Hidden beneath the concrete slabs and grass is chemical waste that was collected in the first partial clean-up of the 1976 environmental disaster. Malavasi describes how leftover arsenic and culled cattle lie within.

Only 400 metres separate the industrial estate from the Monticchio neighbourhood on Manfredonia’s northeast edge. In 1998, the area was declared a “site of national interest” by ministerial decree: it is one of the 40 places in Italy considered potentially contaminated and awaiting clean-up. For years, residents have been trying to bring the danger presented by the area to the attention of the institutions. Rosa and her fellow activists are still fighting for the clean-up to be completed. They have founded Bianca Lancia, a successor to the Donne di Manfredonia. They are the city’s living history, encouraging the transferral of collective memory between the generations.

Sociologist Silvio Cavicchia tells of how the struggle which started back in 1988 is not just a mass mobilisation, but also a movement made up of individual behaviour and awareness: “Environmental awareness is a legacy that lives on among the inhabitants of Manfredonia.”

In 2016, when locals were asked to vote in a consultative referendum on the construction of a coastal gas storage depot by Energas S.p.A., almost 96 per cent of voters were opposed. In the run up to the referendum, debates on the Energas plant re-opened old wounds and made younger residents aware of the city’s history.

In 2019, in the wake of the global Fridays for Future movement, the young people of Manfredonia also took to the streets. They were wearing masks printed with the face of Nicola Lovecchio, a former worker at the petrochemical plant who, with oncologist Maurizio Portaluri by his side, sued the company in 1996 for exposing him to arsenic leaks that were believed to have caused his lung cancer. Lovecchio died in 1997 but the lawsuit continued, only to be dismissed by the court a few years later. Lovecchio’s story was seen as the latest in a long line of betrayals.

Meanwhile, a new environmental consciousness has begun to take hold down at the port. A group of fishermen is working with Legambiente, Italy’s leading environmental NGO, to fight marine pollution: they talk of rubbish lining the seabed, microplastics in fish, and the myriad mussel farms clogging up the sea. They give Legambiente the loggerhead sea turtles that get accidentally caught in trawler nets. With their help, the organisation saves on average 150 turtles a year.

Yet despite all the organising and increased awareness, the collective conscience of local residents has been unable to turn the politics of the region around. The question remains: what went wrong?

Cavicchia explains how nepotistic power structures and clientelism are now endemic within institutions, preventing environmental awareness from gaining a foothold. The role played by the mafia in the EniChem affair, and the abusive use of industrial areas, remains little discussed: “Nobody talks about it, nobody wanted to know a thing, not even the prefect or police chiefs. And yet there are piles and piles of documents that prove mafia infiltration.” The many threats and cars burned out at the time of the 1988 protests taught people that environmental interests are diametrically opposed to those of organised crime. In October 2019, wiretaps confirming the links between local government and the mafia led to the dissolution of the municipal council for racketeering.

The many threats and cars burned out at the time of the 1988 protests taught people that environmental interests are diametrically opposed to those of organised crime.

With few alternatives, Cavicchia fears that the clan-based system of power is becoming even more firmly entrenched. Government institutions are mistrusted, and the death of political parties (the early 1990s’ collapse of the two giants of postwar Italy, the Christian Democrats and the Communists, left an enduring vacuum in Italian politics and society) brought a loss of direction for the community. Without a common goal into which its efforts can be channelled, the collective risks wasting its energy. In a land that has lost its bearings, strongholds of community resistance, such as schools or parish churches, can offer new possibilities for social and political change.

Homilies at the grassroots

On the outermost edge of Manfredonia, Father Salvatore Miscio ministers in the Sacra Famiglia church, a modern building converted into a neighbourhood house of worship. A calm figure, Father Salvatore is a lynchpin of the local community. Together with the archbishop of Manfredonia, the Most Reverend Franco Moscone, he started the Manfredonia rialzati (Manfredonia, pick yourself up) movement. Drawing on the Church’s strong roots in the region, they have created a space for discussion and grassroots democracy.

“It’s a bottom-up movement that tries to mobilise people, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, addressing the question of active citizenship to create a new awareness of the public good.” Father Salvatore sees the movement as a possible cure for all the historical and cultural damage that allowed omertà (code of silence) and clientelism to take root.

Through the movement, Archbishop Franco and Father Salvatore talk to local people about the political and social rifts in the region, including the business of cleaning up the EniChem site and municipal collusion with the mafia. Father Salvatore explains that Puglia’s Sacra Corona Unita – Italy’s “fourth mafia” – is an organisation that feeds on social apathy and “the fear that these criminal mechanisms are unassailable”. The role of the movement is also to resist the creation of a culture in which clans are seen to be closer to the people than the state.

In many regions of southern Italy, Christianity is still a powerful force and places of worship also serve as spaces for communities to mobilise and collectively express themselves. But with their doors closed by the pandemic, the lack of spaces to gather risks favouring the atomisation of society, building walls between individuals and communities.

Environmental movements are also centripetal forces, restoring a sense of belonging and pushing the community to re-assert control over its territory. In Manfredonia, the unfinished business of the clean-up is holding the city back. It also exposes the weaknesses of a social system that residents are struggling to eradicate. After all, for local people, their environmental battle represents a form of liberation from a long-standing legacy of exploitation. For the Gargano region, a sustainable local economy means taking back control of the land and wresting it away from misuse by organised crime and polluting industries.

In Manfredonia, the environment is first and foremost a political and social problem: it is born out of the mafia culture of omertà, indifference to the public good, and clientelist politics. In a context in which institutional forms of power are resistant to change, Manfredonia’s civil society has developed new forms of grassroots democracy to fight back.

As they sought environmental justice, the people of Manfredonia were confronted with fundamental questions about their community, questions that went far beyond the EniChem environmental disaster – from the liberation of a group of women in late 1980s Puglia to grassroots democratic demands that continue to this day. A series of human stories tells us how, historically, even in different places and at different times, environmental injustice stems above all from democratic exclusion. In Manfredonia, everything started with the political disenfranchisement of a population forced to give up control over its land until the spectre of a poison ship on the horizon triggered a new, bottom-up democratic struggle – a movement to protect land and life that continues to be passed from one generation to the next.

[1] Giuseppe de Filippo (2012). “Indagini epidemiologiche 17 SIN, bibliografia e dati Manfredonia (V)”. Stato Quotidiano. 18 September 2012. Available at <https://bit.ly/3h3MIlr>.

[2] Giulia Malavasi (2016). “Manfredonia (Southern Italy): a continuous catastrophe, newfound citizenship, and removal”. Epidemiologia & Prevenzione, 40(6), pp. 389-394. Available at <https://bit.ly/3tcwTuP>.

[3] Ibid.

Photos by Federico Ambrosini. All rights reserved.