Developments in southern Europe will influence the EU’s political trajectory in the years to come. If progressives are to challenge the Right’s dominance in Italy and Greece, they need to find unity in fragmentation, following the examples of Spain and Portugal.

In the big picture of European politics, Spain and Italy couldn’t be further away from each other. In Spain, the most left-wing EU government has reconfirmed a broad progressive majority, while in Italy a national-conservative government leads Europe’s reactionary movement. Yet, in terms of electorate, Spain and Italy are closer than a first look might suggest. In their last elections, the right-wing camp reached 44 per cent of the vote in Italy and 45 per cent in Spain.

The eurozone crisis happened, and the established ways of doing politics were broken.

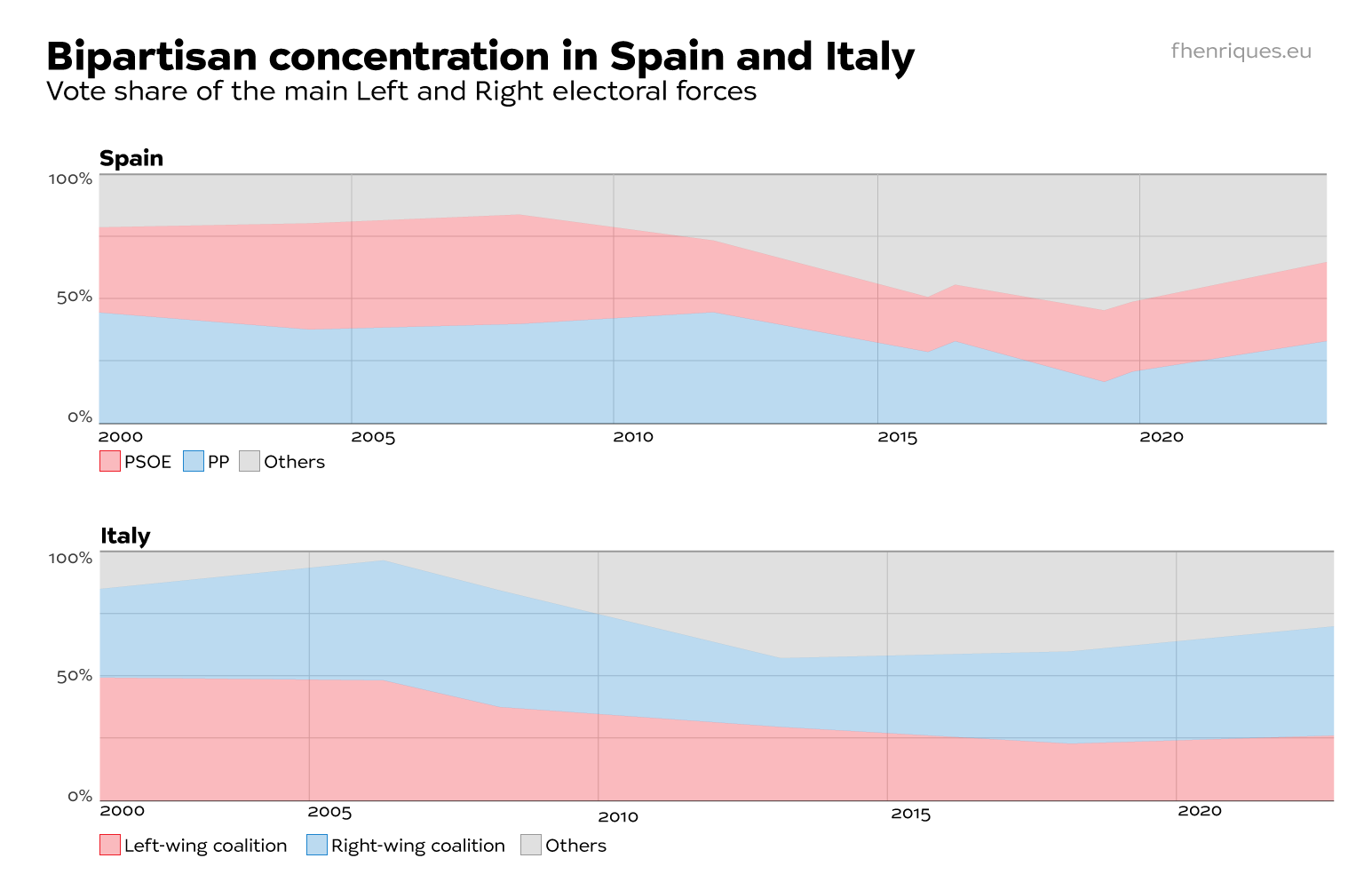

The political landscape of both countries went through a significant fragmentation in recent years. In Spain, the socialist PSOE and the conservative PP used to attract 80 to 90 per cent of the vote. Similarly, the two broad coalitions led by the centre-left Democratic Party (PD) and the centre-right Forza Italia (and their predecessors) would monopolise Italy’s electorate. Then the eurozone crisis happened, and the established ways of doing politics were broken.

Competition and radicalisation

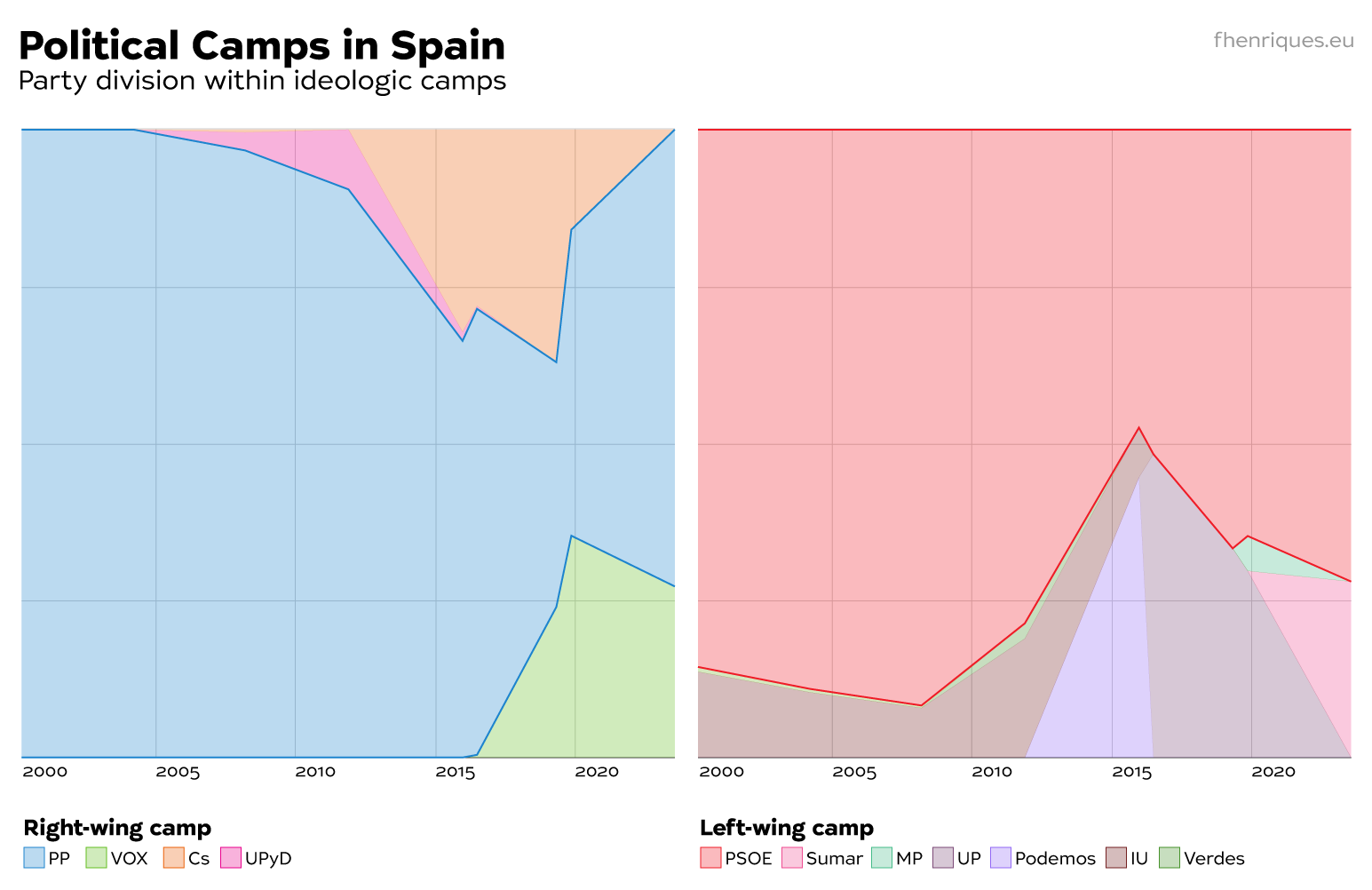

In Spain, this shift led to a bigger plurality within the two main blocs. The Left’s more radical wing grew stronger and evolved from Izquierda Unida into Podemos and now Sumar; on the Right, PP had to compete and ally first with liberal-conservative UPyD and Ciudadanos, and then with far-right VOX.

A Spanish peculiarity is the strength of regional parties, which attract around 10 per cent of the vote. By forming alliances with national-centralist parties, the PP lost any chance of building coalitions with the regionalist right. This new reality helped socialist Pedro Sánchez form a government in 2018, and is now crystallised in a progressive camp stretching from the Left to the regionalist centre-right.

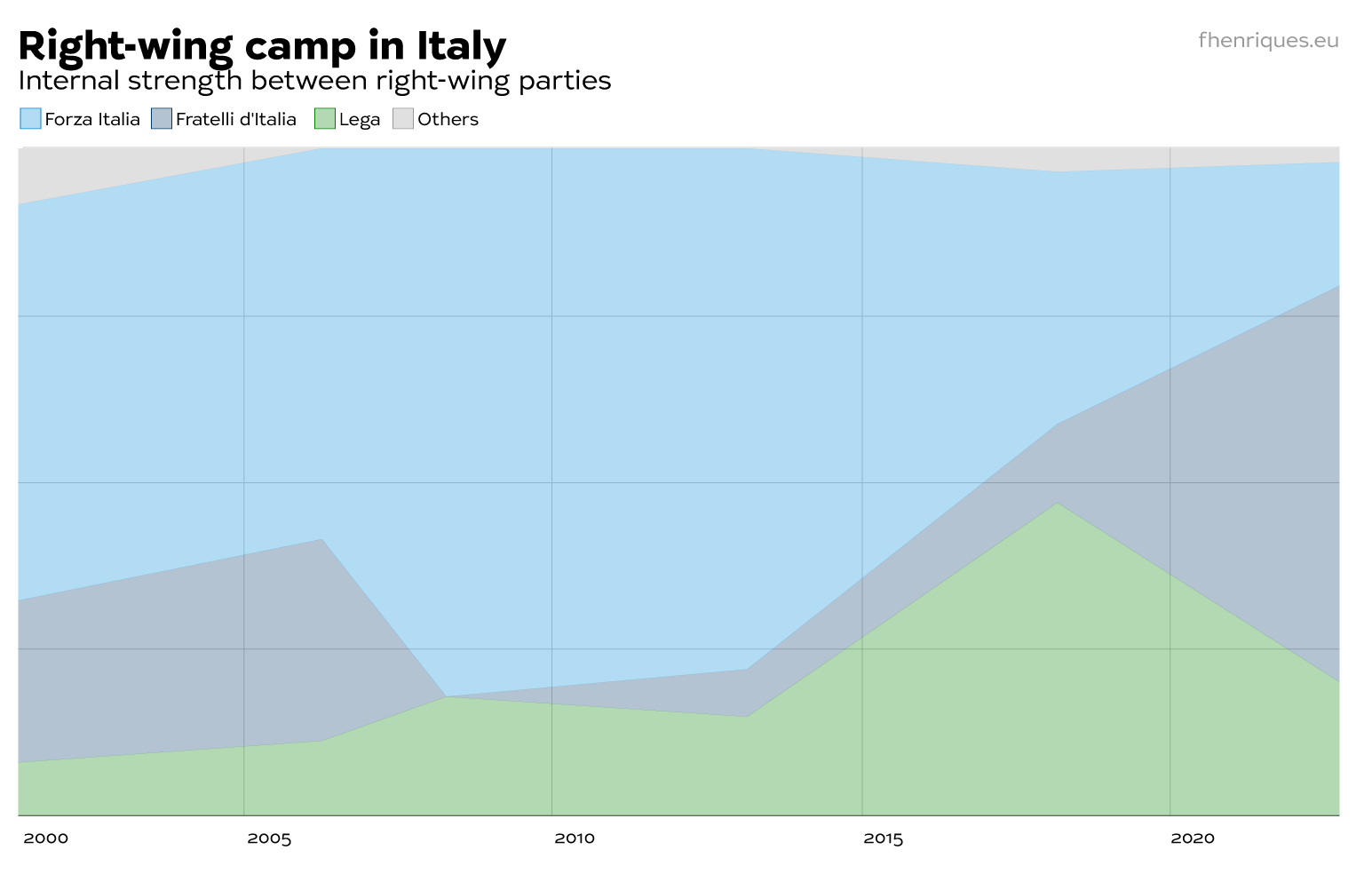

In Italy, plurality was always a given. What has changed is the balance of power within the Right; in 2018, the League’s Matteo Salvini (a regionalist turned nationalist) put an end to two decades of Silvio Berlusconi’s dominance; in 2022, post-fascist Brothers of Italy’s Giorgia Meloni was elected prime minister. The Right radicalised itself from within.

Meanwhile, the opposition is deeply divided between the centre-left PD, the Five Star Movement, and a fratricide centrist liberal camp. In an electoral system that rewards unity, the right-wing coalition won 60 per cent of the seats with just 44 per cent of the vote.

In the fragmented political landscape of both countries, it is no longer enough for centre-left and centre-right parties to convince the electorate to go to vote, instead of abstaining, and to persuade the few centrist voters to choose them instead of their rival. The path to victory is now about building alliances and motivating the electorate that a win is possible. In this new reality, Spanish progressives managed to rally voters against the threat of the far right, and to gather support from the regionalist centre-right. In Italy, a divided progressive camp allowed Giorgia Meloni to walk into power unopposed.

The rest of southern Europe has gone through equally substantial political changes in the last years. In Portugal, like in Spain, the right-wing camp, which had been united since the transition to democracy in the 1970s, is now marked by internal competition between the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD), the Liberal Initiative (IL) and the far-right Chega, while parties on the Left, more used to multi-centrism, learned to cooperate.

In Greece, a consequence of the economic crisis has been lower turnout. The decline in voter participation (from 74 per cent in 2007 to 61 and 50 per cent in May and June 2023, respectively) has affected mostly the Left. Between 2009 and 2023, progressives lost almost 2 million votes, or half of their electorate, while the Right remained stable at around 2.7 million votes. This allowed conservative New Democracy to gain an absolute majority in 2023, even though the right camp is more radicalised and atomised than before: the far right, which had no party-political strength in the early 2000s, now represents more than half a million voters across three parliamentary parties (Greek Solution, Spartans, and Niki).

Implications for Europe

Can Europe have a progressive breakthrough in 2024? The answer will partly depend on the mobilisation of progressive voters in southern Europe, and which parties will be willing to be part of a progressive coalition that breaks the sectarianism of the current groups. As two of Europe’s largest countries, Spain and Italy will play a big role. The inclusion of Italy’s Five Star Movement in a European progressive camp might prove decisive.

Can Europe have a progressive breakthrough in 2024? The answer will partly depend on the mobilisation of progressive voters in southern Europe.

The role of the liberal camp cannot be underplayed either. While the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) freely flirts with the national conservatives for a new reactionary alliance, European liberals and centrists still refuse to position themselves clearly. In southern Europe, the liberal camp (when it exists) is small, but it’s still more conservative-liberal and right-wing than in the rest of the continent: in Spain, Ciudadanos led efforts to engage with the far right; in Italy, both Azione and Italia Viva behave more like conservatives than liberals.

Greens will have a key role too. Southern European Green parties currently have no representation in the EU Parliament, and their weight on EU politics has been minimal for decades. However, the green movement in Spain and Portugal has grown significantly in the last few years. Spain’s Sumar, which brings together Greens and progressive leftists, and Portugal’s LIVRE and PAN, could deliver a relevant Green delegation to Brussels. In Italy, Europa Verde has returned to parliament and has a chance of crossing the 4 per cent threshold. In Greece, the collapse of Syriza under a new centrist leadership could open the space for new progressive forces.

The four months that separate us from the European elections may already provide some answers. In February, Galicians in northwestern Spain will go to the polls for a regional election that could see a progressive alliance take power after 34 years of almost uninterrupted conservative government. In March, Portugal will hold early elections after a corruption scandal that brought down socialist Prime Minister António Costa. The question is whether Portuguese progressives will manage to mobilise their electorate after eight years of socialist governments, and whether the centre-right will keep its cordon sanitaire against the far right intact.