Since it was introduced a decade ago, the choice of the “Spitzenkandidaten” for the Commission presidency ahead of the EU elections has often been characterised as both technocratic and pointless. But the EU is no absolute monarchy: in democracy, choices are made through political compromise.

In the era of social media and infotainment, every political battle is narrated as a final reckoning that will either solve all problems or end the world. EU democracy, of course, is not immune to this maximalism. A good example of this trend is the debate surrounding the lead candidate process, through which European political parties nominate their contenders for the Commission presidency ahead of the EU elections. In 2019, when Ursula von der Leyen got the EU’s top job instead of Manfred Weber, the chosen candidate of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), the entire process was pronounced dead.

And yet, five years later, it is alive and well. The Socialists have recently nominated Commissioner Nicolas Schmit; the Greens have elected their lead candidate duo, MEPs Terry Reintke and Bas Eickhout; the Liberals and the Left are expected to make their choice soon; and the EPP will likely support Ursula von der Leyen for a second mandate. In the next months, lead candidates will campaign all over Europe on an electoral manifesto that unites their political family.

Clearly, the lead candidate process was more resilient than some expected. But is it also democratic?

Longstanding scepticism

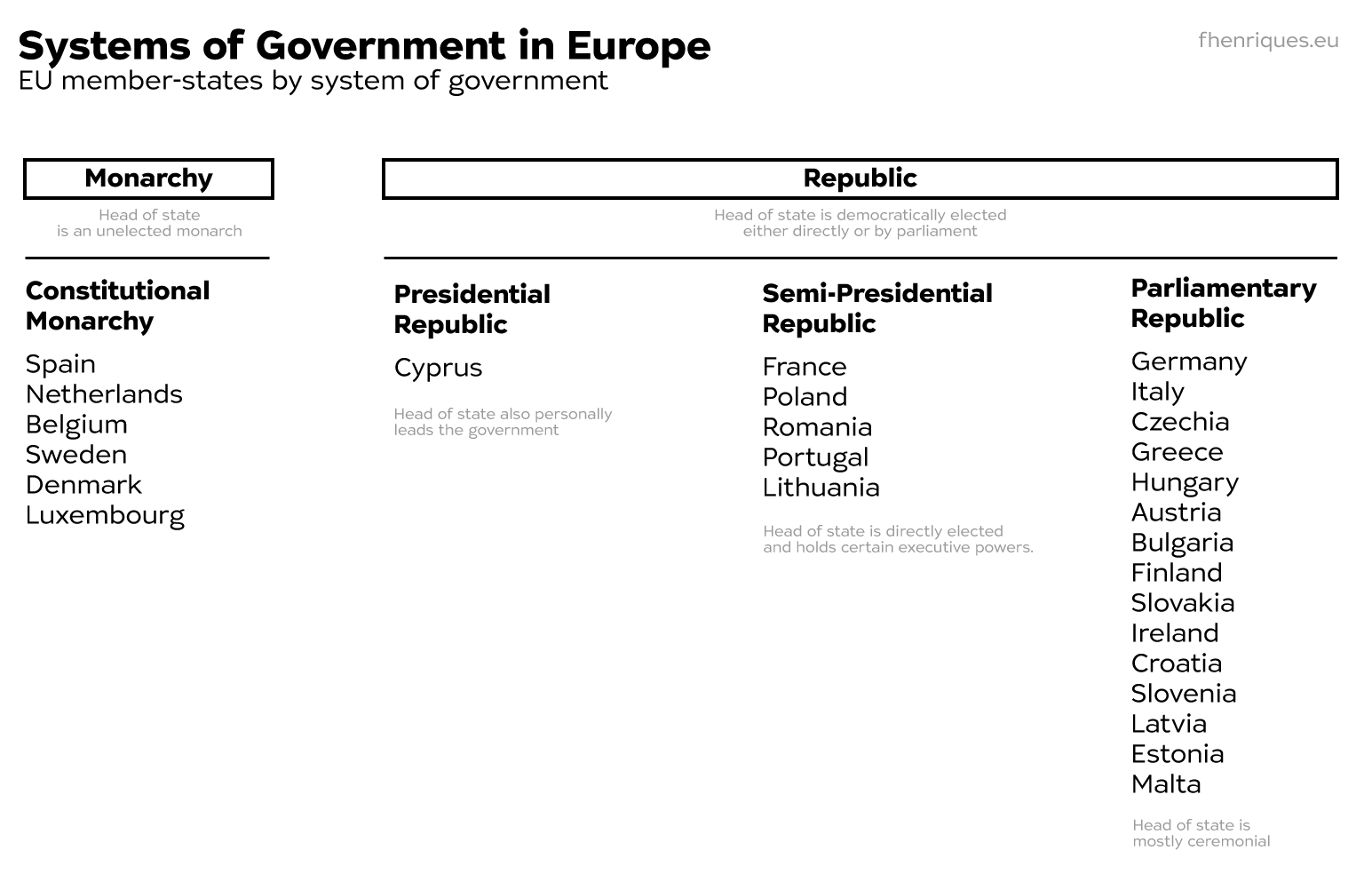

Most states in the EU are based on parliamentarism, meaning that the parliament is at the centre of politics. The head of state – a president or a monarch – has restricted powers, and the government derives its democratic legitimacy from the parliament.

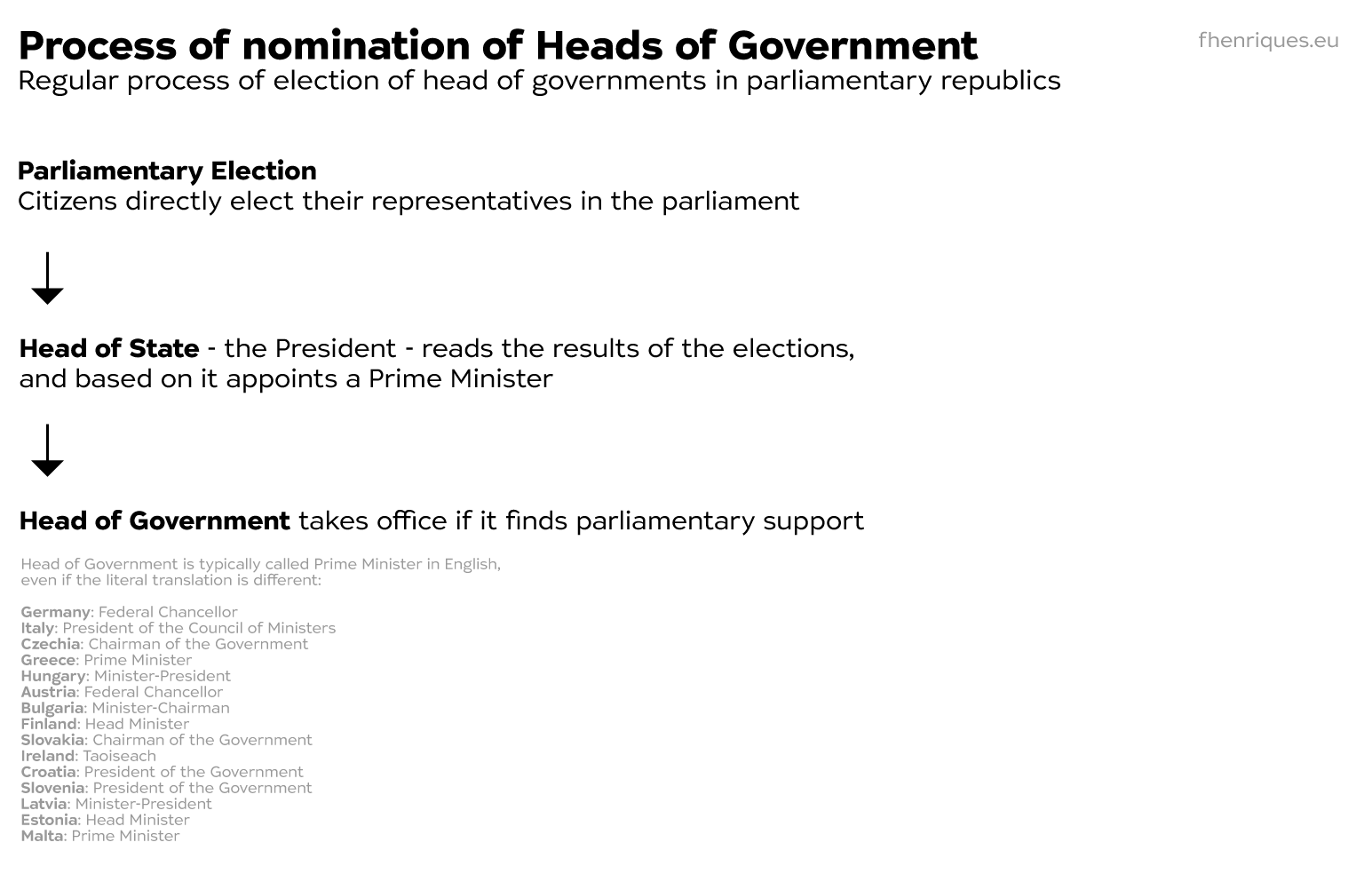

In parliamentary systems within the EU, heads of government (whether they are called prime minister, minister-president, president of the government or of the council of minister, chancellor, or taoiseach) are not elected into office directly by “the people”, but appointed by the head of state, usually after consulting the parliament.

The European Union is also a parliamentary system. The Commission president is the head of government, commissioners are the equivalent of government ministers, and the powers of the head of state lie with the European Council, which brings together the 27 national leaders.

That the names and roles of these institutions are sometimes confusing is not by chance. As with many things in European politics, the current institutional set-up is the result of compromise between those who wanted to build a European democracy and those, led by always-eurosceptic Britain, who preferred a European technocracy under the control of national powers. For every step that brought us closer to a more complete European democracy, the advocates of national sovereignty made sure to make the process more difficult to understand. Yes, Europe could have its own government, but it would be called a Commission and have limited authority. Sure, Europe could have its elected parliament, but without the power to directly initiate legislation.

For every step that brought us closer to a more complete European democracy, the advocates of national sovereignty made sure to make the process more difficult to understand.

When it comes to the election of the European Commission president, however, the process is in all respects similar to its national equivalent: EU citizens vote in the European elections, the European Council proposes a candidate based on the result, and then the European Parliament approves it.

In 2014 something changed. The lead candidate system was introduced to establish a clearer link between national parties of the same European political family, EU elections, and EU institutions. European-level political parties announced their candidates for President of the European Commission ahead of the vote and sent them campaigning across Europe.

The EPP and the Socialists selected Jean-Claude Juncker and Martin Schulz as their lead candidates. Smaller parties like the Liberals, Greens, and Left also chose their contenders. The EPP won the election, the main political parties agreed on a new grand coalition, and Juncker became President of the Commission. The process was repeated in 2019 with Manfred Weber (EPP) and Frans Timmermans (Socialists) as the top contenders for the presidency. The Liberals, Greens, Left and now also Conservatives followed suit with their nominees. Eventually, the EPP’s von der Leyen got the job, and obituaries for the whole process started to appear.

The process had been surrounded by scepticism even before 2019. Once again, language was part of the problem: many in the EU bubble and national media circles use the German “Spitzenkandidat” instead of the equivalent in their respective European language – lead candidate, candidat tête de liste, capolista, candidato principal, czołowy kandydat, and so on. This contributed to making the process sound complicated and inaccessible to EU voters.

In 2019, what brought von der Leyen to the helm of the Commission was not the failure of the process, but democratic parliamentarism in action. Unlike his predecessor, Weber was incapable of uniting a majority around him. Socialists and Liberals, and even parts of his own political family, did not trust him to become Commission president. This, together with the fact that the EPP had won the elections and that the Socialists refused to work towards finding an alternative majority, meant that the EPP was forced to find a different candidate.

Something similar had happened in Italy after the 2013 and 2018 elections. In both cases, the lead candidates of the parties that won the elections – the centre-left’s Pier Luigi Bersani and Luigi di Maio of the Five Star Movement, respectively – did not find a majority to form a government, leading to Enrico Letta and Giuseppe Conte becoming prime ministers. Italian democracy did not end because of this, and neither did European democracy in 2019.

Democracy in progress

Since 1979, when the first European elections took place, European democracy has evolved in small steps. The lead candidate system is one of them, and it will continue working as it has done for more than a decade.

To prepare for enlargement in the Western Balkans and further east in the next decade, the EU needs to strengthen its democratic achievements and become more reflective of its diversity.

Just like national democracies, European democracy is still flawed. EU election campaigns are nationally minded, European political parties do not get enough media attention, and their internal processes for choosing lead candidates are often untransparent or not representative of the Union’s diversity. The fact that most lead candidates for June’s elections come from either Germany or the Benelux (as was the case in previous elections too) shows that the process is controlled by party elites.

For 2024, the die is cast. But to prepare for enlargement in the Western Balkans and further east in the next decade, the EU needs to strengthen its democratic achievements and become more reflective of its diversity. As Altiero Spinelli said, totalitarianism is not the outcome of an incurable disease, but of an organism that renounces to defend itself. A healthy European democracy is the strongest guarantee against resurging nationalism and geopolitical turmoil.