Low voter participation in EU elections, reflecting the preeminence of national over European identity, can undermine the democratic legitimacy of the EU Parliament. Could progressive Europeanisation and lowering the voting age help bring Europe closer to its citizens?

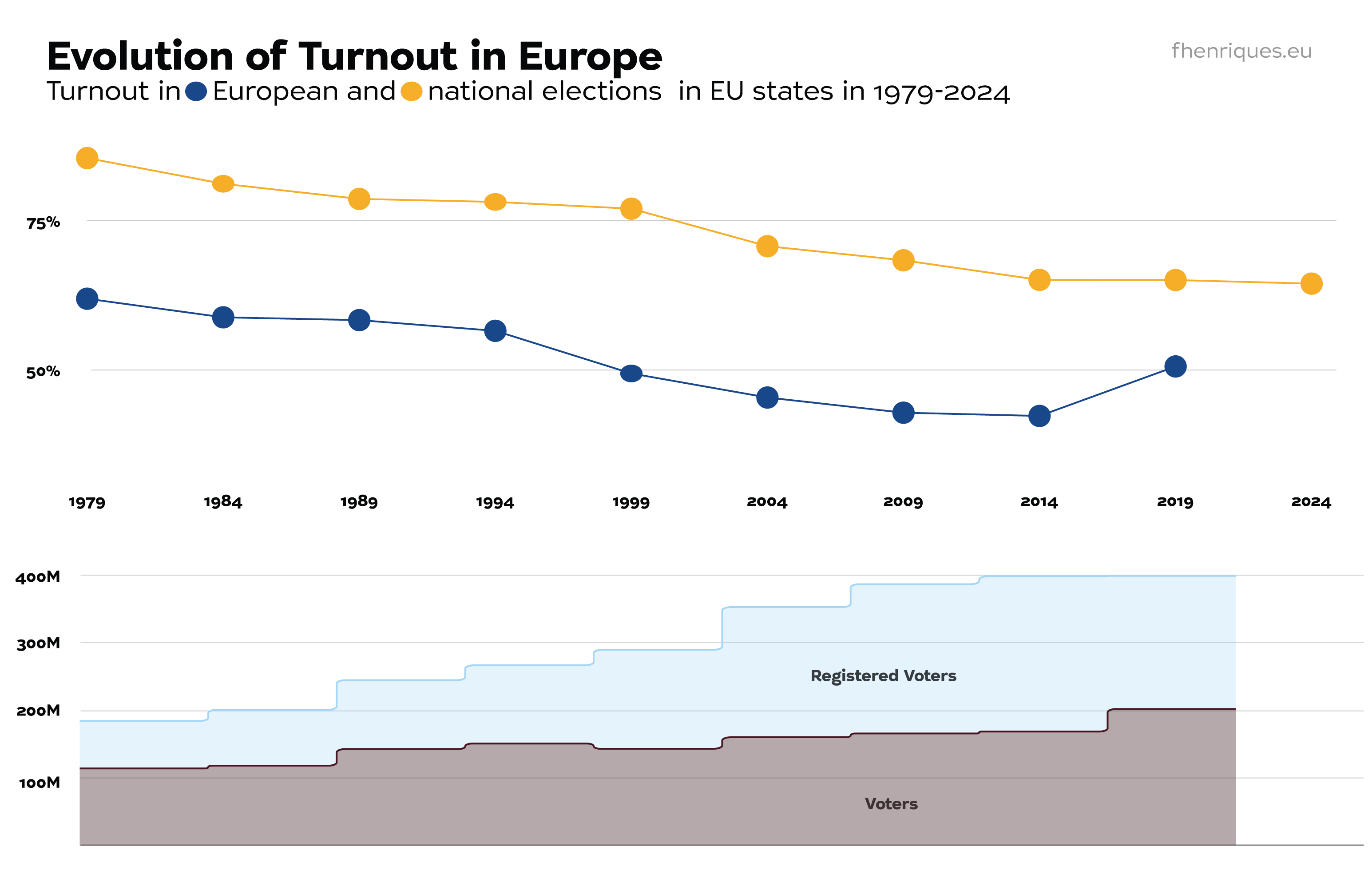

When talking about European politics, you’ll often hear that “EU elections have low turnout”. There is some truth to that: in 2019, only half of the almost 400 million eligible voters cast their ballots. In 2014, the turnout was even lower, at 42 per cent.

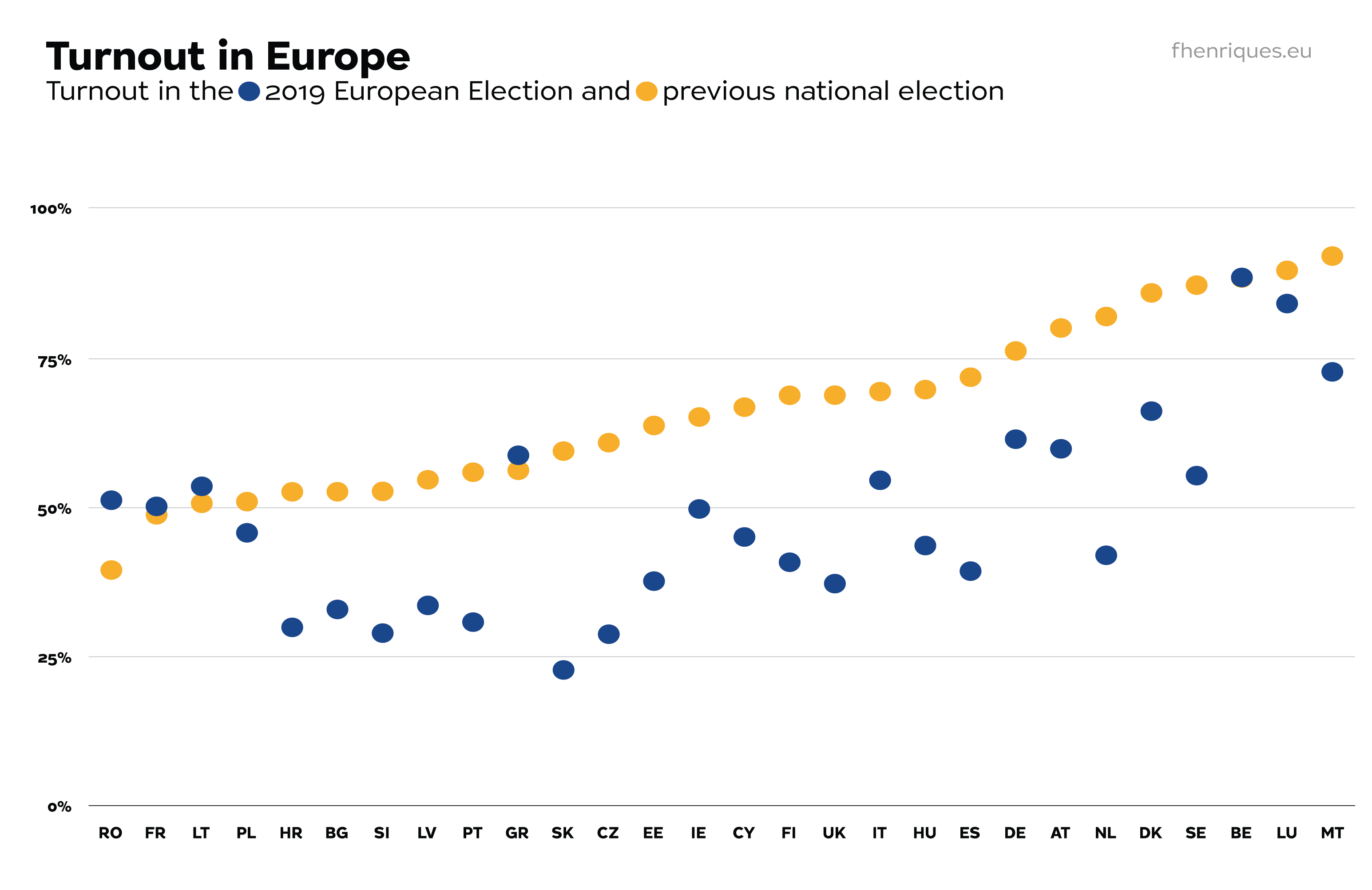

Voting behaviour is not uniform across the continent. In Belgium, where voting is compulsory, turnout is close to 100 per cent. In the last EU elections, Romania had a comparatively shocking 51 per cent turnout. This number, however, appears much higher when compared to the 32 per cent turnout in the Romanian parliamentary elections the following year. In Slovakia, on the other hand, less than 23 per cent voted in the last EU elections, compared with 65 per cent in the national parliamentary elections that same year.

A closer look at turnout numbers can help us better understand European democracy. First, we should dispel the notion that European elections having lower turnout than national elections is in itself a democratic problem. Identity leads political action, and national identity remains prominent among EU citizens: 91 per cent feel attached to their country, while 59 per cent feel attached to the European Union, and only 72 per cent of citizens of the EU identify as such.

In global history terms, there’s nothing to worry about. The European Union is a 66-year-old continental entity built on pre-existing national realities. For comparison, the United States of America was founded in 1776, and only since 1968 has national identity become more relevant than state identity. It took US citizens almost 200 years to identify more as “Americans” than as Californians, New Yorkers, or Floridians.

The prominence of national identity is also visible at the local level, where elections typically have lower turnout. The distribution of power has an impact on turnout too: in France, where the president is the main political leader, the 2022 presidential elections attracted 25 per cent more voters than the legislative elections of the same year.

At the EU level, turnout has mostly decreased from 1979 to the present. Partly, this is because Eastern European countries, which joined the EU in 2004 or later, usually have lower voter participation than their Western counterparts. However, some Western European countries have also influenced this trend. EU election turnout in France fell by 10 points from 1979 to 2019, while it fell by more than 30 points in national parliamentary elections over the same period. Italy abolished mandatory voting in the 1990s, and turnout went from 81 per cent in 1989 to 54 per cent in 2019. Again, a similar trend occurred in national elections.

Voting is an essential component of a healthy democracy, and we should make sure that as many people as possible choose their representatives by casting their votes.

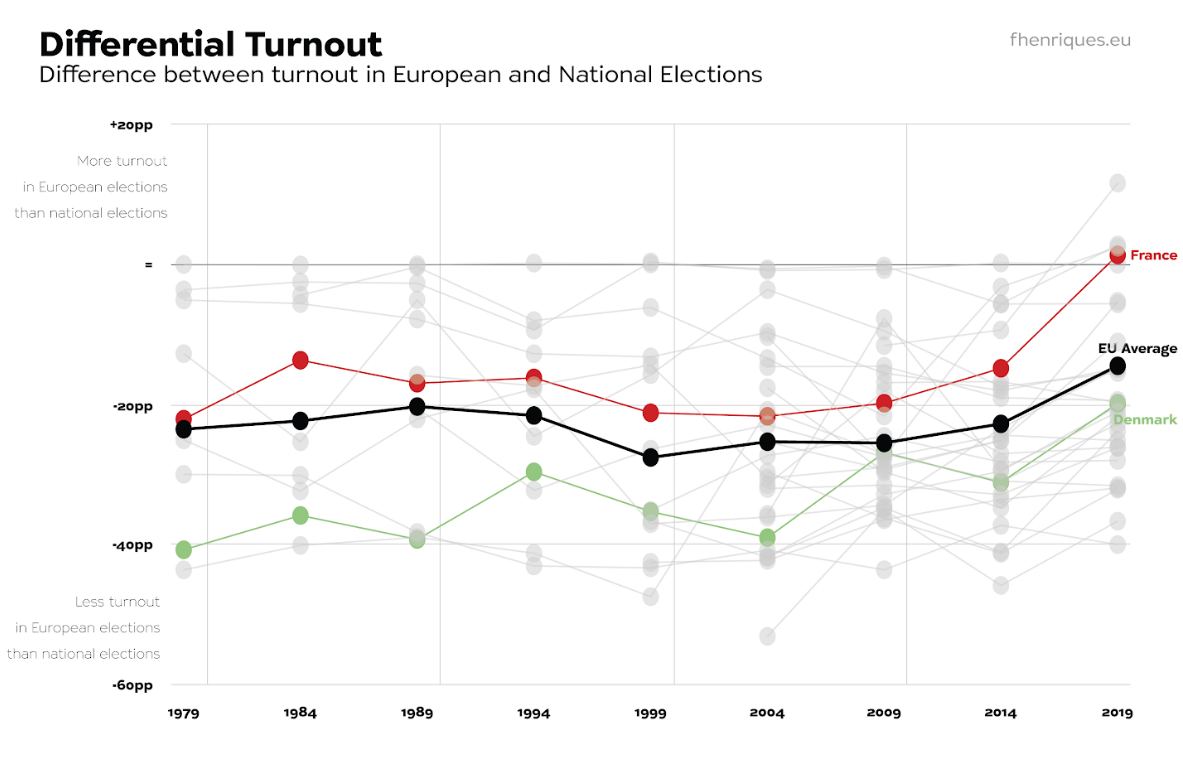

Voter participation in EU elections has traditionally been about 20 per cent lower than in national parliamentary elections. Since 1999, this difference has narrowed, especially in some countries. In France [red], the 2019 European elections had a similar turnout as the 2017 national elections; in Denmark [green], national turnout has remained stable at around 85 per cent while it grew in European elections from 45 per cent in 1979 to 66 per cent in 2019.

If turnout has been influenced by EU enlargement and long-term trends that also affect national elections, then what does it tell us about European democracy?

Low voter participation can no doubt be a democratic problem. When only 20 or 30 per cent of citizens exercise their right to vote, as was the case in Slovenia, Slovakia, Portugal, Latvia, Czechia, Croatia and Bulgaria in 2019, the result represents a minority of the population. Tackling this issue of democratic legitimacy demands that political parties take European elections seriously – starting from the lead candidate process – and that the media do their part in nurturing European democracy. But as the EU prepares to enlarge to the Western Balkans and further East, institutional reform is also needed to simplify processes and make them more understandable, more political, and less bureaucratic.

Voting is an essential component of a healthy democracy, and we should make sure that as many people as possible choose their representatives by casting their votes. Voting should be made easy, for instance by abolishing the need to pre-register and expanding the possibility of voting early.

However, framing turnout as the single indicator of democracy is misleading. Sometimes, high voter participation is a consequence or a harbinger of democratic backsliding. In Poland, the great mobilisation of young people and women last October was the reaction to almost a decade of radical right-wing governments which undermined the rule of law and women’s rights. More recently, in Portugal, many citizens with anti-democratic views turned up to vote for the first time for a far-right party. In both countries, higher turnout (+13 per cent in Poland, +9 per cent in Portugal compared to previous elections) was linked to growing polarisation.

Young people are the most “European” generation, born and raised in an interconnected world.

In other cases, lower turnout can go hand in hand with higher democratic participation. For example, 16 and 17-year-olds will be allowed to vote in the 2024 European elections in Germany, Austria, Belgium, Malta, and Greece. Even if voting at 16 might result in lower participation (turnout is often lower among younger voters), this is a democratic improvement that gives political representation to a group that has a fundamental right to it. In a sense, young people are the most “European” generation, born and raised in an interconnected world. For them, Europe is not a “project of peace” or the Erasmus programme, but the multifaceted reality that we live in.

The last decade has also shown how young people can drive political change. Youth-led demonstrations and movements shaped politics ahead of the 2019 European elections. Extending the right to vote to 16-year-olds is therefore only logical, and can be complemented by political and civic education from an early age. This way, perhaps, voter turnout will also increase in the long run.