While conservatives are still dominant in eastern Europe, most illiberal parties are struggling. If progressives succeed in mobilising the electorate in traditionally low-turnout countries, the 2024 EU elections could mark a change.

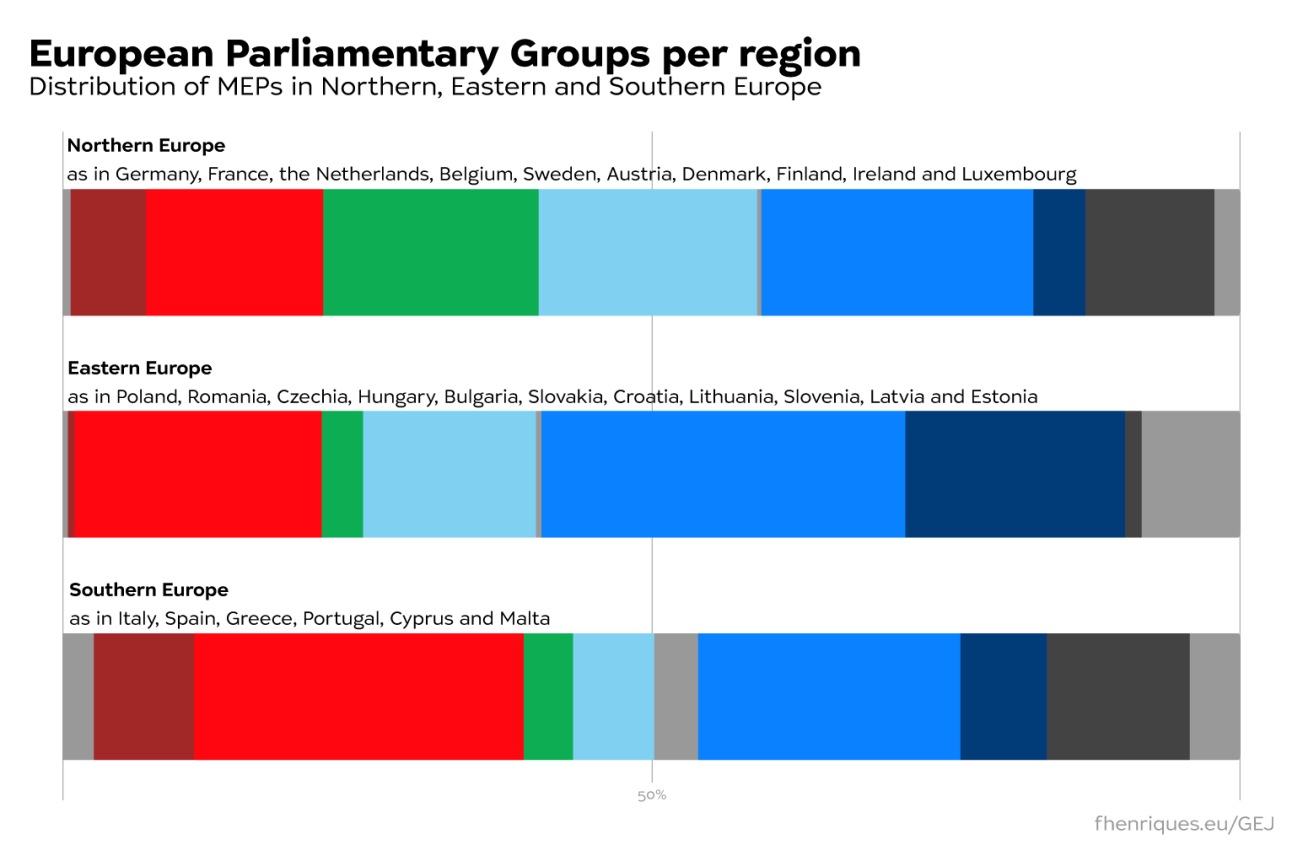

If we divide the EU into three geographical regions, eastern Europe is arguably the most conservative one. In the current EU Parliament, more than 60 per cent of the MEPs elected in eastern European member states sit in conservative and right-wing groups: the European People’s Party (EPP), the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), and Identity and Democracy (ID).

The conservative orientation of eastern Europe was also visible in the von der Leyen Commission and which policy areas were assigned to the eastern Commissioners, like Poland getting agriculture or Croatia’s conservatives getting the newly established demography portfolio.

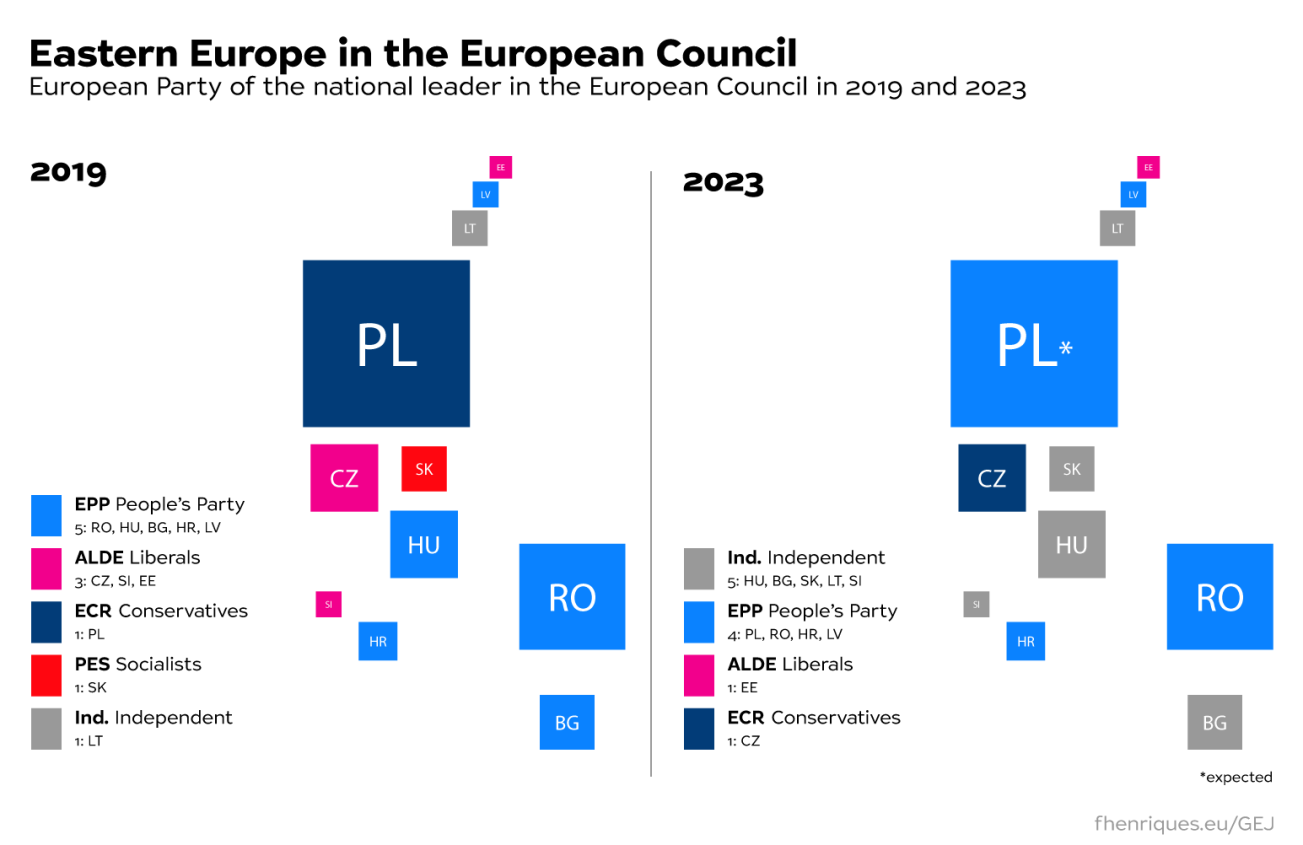

Even when right-wing populists are ousted in eastern European countries, it is often by other conservative forces. Last month, Law and Justice’s (PiS) Morawiecki-Kaczyński duo was defeated in Poland, as was Andrej Babiš in 2021 in the Czech Republic. In both cases, their challengers came from the democratic Right – the EPP’s Donald Tusk in Poland and the ECR’s Petr Fiala in Czechia.

Eastern Europe will be key for the realignment of the bloc’s illiberal forces. Poland’s PiS has led the ECR since Brexit, but will now return to opposition domestically. Hungary’s Fidesz decided to leave the EPP in 2021, choosing to jump rather than be pushed. Slovakia’s pro-Putin, social-democratic populist party Smer has been suspended from the European Socialists after winning the parliamentary elections in September. The Czech Republic’s ANO party of former Prime Minister Babiš is at odds with the European liberals of ALDE. All these developments create an opening on the illiberal front for new alliances at EU level.

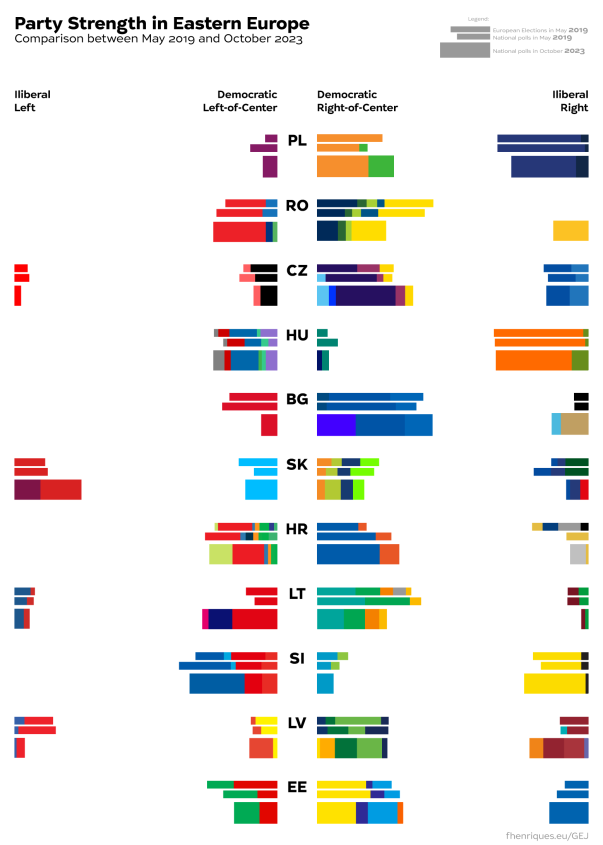

However, contrary to the dominant narrative, most illiberal parties across eastern Europe are struggling. Notable exceptions are Romania, where the far-right AUR is polling at around 20 per cent, and Latvia, where the ethnic Russian illiberal Left has joined the ethnic Latvian National Alliance on the far-right of the spectrum.

For 2024, the biggest challenge will be how the new EU Commission president deals with candidates from the likes of Hungary and Slovakia.

In 2019, the worry about illiberal commissioners also led to the nomination of Vera Jourova, a rare liberal in the Czech ANO, or long-time Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič from Slovakia’s Smer-SD, who, despite campaigning in his home country against LGBT+ and women’s rights, has a good reputation in Brussels. For 2024, the biggest challenge will be how the new EU Commission president deals with candidates from the likes of Hungary and Slovakia.

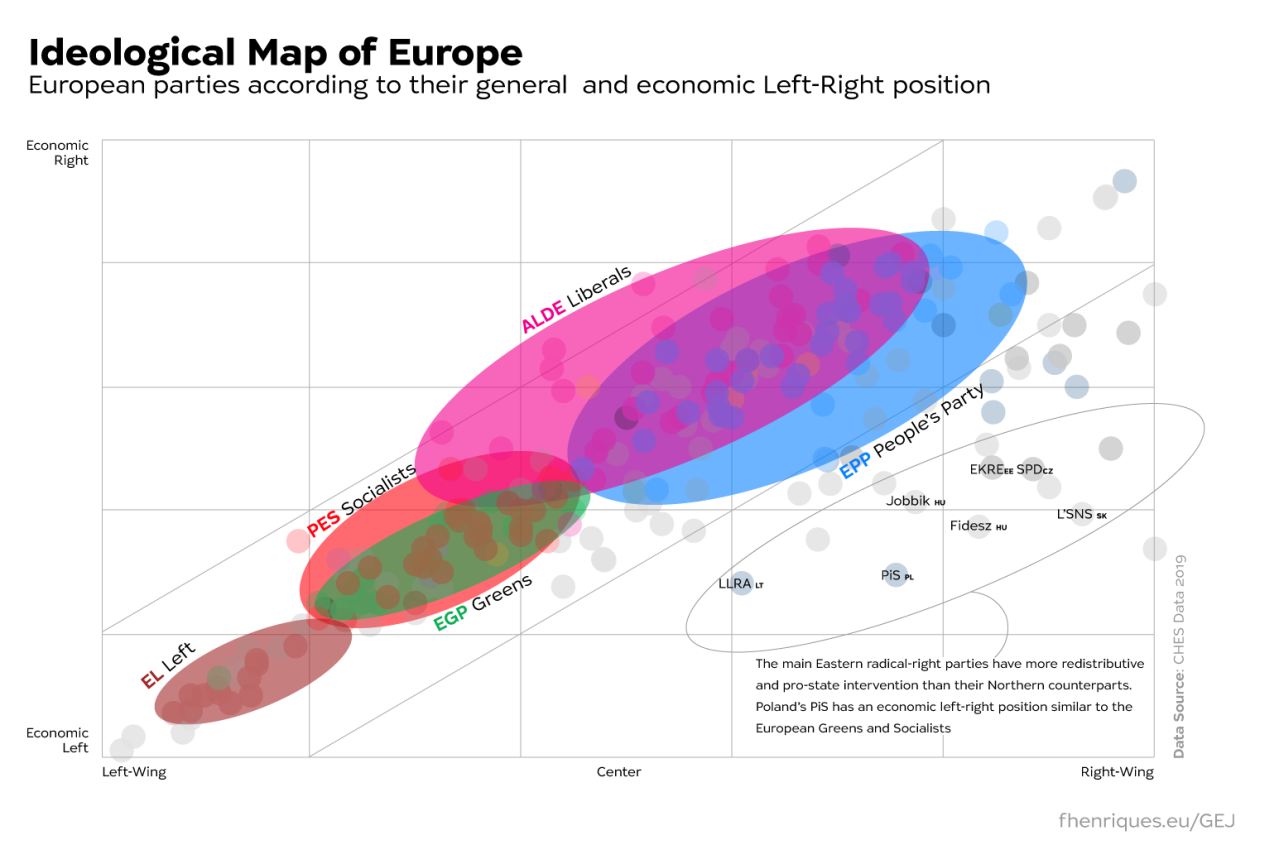

The division of Europe into north, south and east is more arbitrary geographically than it is in terms of recent political history. All eastern European countries were under Communist rule for most of the period between 1945 and 1990. In the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, social democracy entered its peak Third Way centrism phase. State-managed economies throughout Eastern Europe were liberalised. With social protection systems much undermined, the post-communist Left in the East became discredited, associated with neoliberalism and mired in corruption.

This has led to the radical Right in eastern Europe being less neoliberal and more socially minded than most other political forces, covering in part an ideological space that would normally be claimed by the Left. Poland’s PiS, for example, has delivered during its almost 10 years in power some key economic redistribution measures, such as the Family 500+ programme to reduce child poverty and the lowering of the retirement age.

Across the region, the progressive camp has either stagnated or lost relevance. Traditional social-democratic parties have lost space and progressive liberal forces have not managed to capture their electorate – with three exceptions: Progresīvie in Latvia, Možemo in Croatia, and the Union of Democrats “For Lithuania” (DSVL).

Progresīvie and Možemo have offered the most left-wing programmes that the democratic space has seen in the last decades in Latvia and Croatia, and have achieved enormous success for such young parties: Progresīvie is in government and Možemo leads Zagreb, the Croatian capital. Unlike their social-democratic peers, these parties are detached from both the Communist past and the neoliberal transition. Through their work in city government, they have proven to be real alternatives.

DSVL is a more centrist party, with quite conservative positions on social issues, as most of Lithuania’s political forces. Yet the three parties might share a common European future: Progresīvie is now a full member of the European Greens, while Mozemo and DSVL have recently applied to join.

If 2024 is to deliver a more progressive EU, eastern Europe will be a key piece in that fight, and that fight is multifaceted.

If 2024 is to deliver a more progressive EU, eastern Europe will be a key piece in that fight, and that fight is multifaceted. Eastern EU members will lead the re-organisation of the right-wing space. In the EPP, eastern European parties are often among the most progressive and pro-democracy and will be the ones pushing back against a potential alliance with the ECR. The opposite is true for the European Socialists, whose more conservative members come from the East.

As for the Greens, in 2024 they could elect an MEP in eastern Europe again after 10 years, namely in Latvia and Croatia. Much will depend on whether progressives will be able to mobilise voters: in 2019, four countries had less than 30 per cent turnout, all in eastern Europe.