The impact of the pandemic and rising inflation are putting further pressure on a housing system that is already in crisis in many countries across Europe. A chronic lack of access to affordable housing is worsening social inequality, while a failure to prioritise sustainability also creates long-term challenges. Solutions such as increased public investment in green and affordable housing and financing low-carbon renovation have been brought to the table, which could be boosted by stronger regulation at a European level.

A perfect storm is brewing for the increasingly limited access to decent, sustainable, and affordable housing. With a decades-long trend of house prices and rents rising faster than inflation, the share of household income spent on accommodation rose on average by five percentage points between 2005 and 2015, amounting to 31 per cent of income for middle-income households across most OECD countries. The situation worsened during the pandemic, with house prices rising 7 per cent on average across Europe. London, Dublin, Amsterdam and Paris are among the least affordable cities, and apartment costs in the Visegrád countries – Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia – have risen to 12 times the average annual salary.

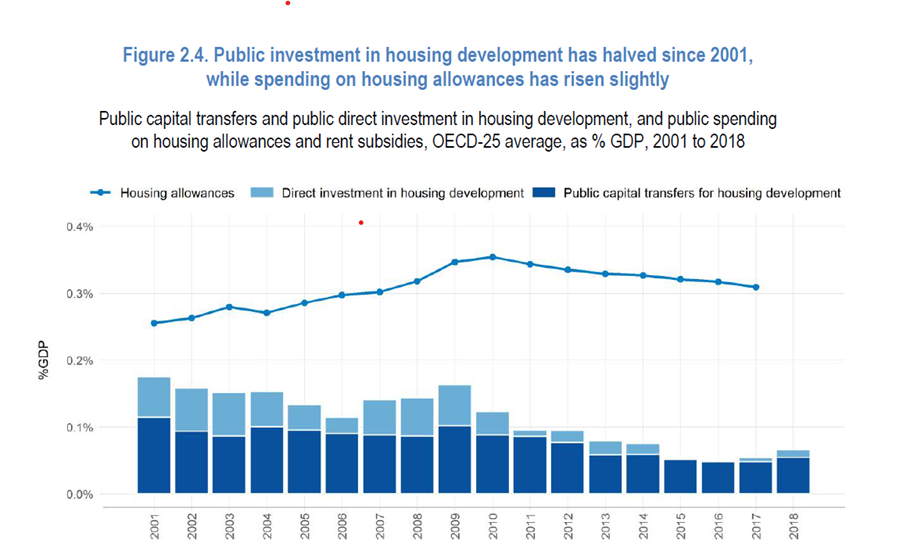

More than 60 per cent of low-income households spend over 40 per cent of their income on housing, and less than half the populations of OECD countries report being satisfied with the availability of good quality, affordable housing in their locality. Housing markets are proving inefficient, in terms of their generalised failure to ensure sufficient housing supply in job-rich urban areas where affordability gaps are the widest. Public investment in housing development has shrunk from 0.17 per cent of GDP in 2001 to 0.06 per cent of GDP in 2018 on average across OECD countries.

The drop in public investment is a result of a widespread policy shift away from social housing construction and towards housing subsidies for low-income renters, according to Boris Cournède, deputy head of OECD’s public economics division. This shift took place over 2000-2010, although “since 2010, housing allowances have edged down too,” he explains. Although post-pandemic recovery packages include the provision of social housing as a priority for several EU member states, including Greece, Ireland, and Luxembourg, there remains a significant funding gap of 10 billion euros per year to meet the objective of low-carbon renovation of the existing stock of affordable homes by 2050.

Greener housing could make all the difference

Alongside the provision of housing, decarbonisation is essential for effective climate action. Residential housing accounts for 17 per cent of energy and process-related emissions of greenhouse gases and 37 per cent of emissions of fine particulate matter globally. Decarbonisation of the building stock has the potential to make a decisive impact. Leading buildings sustainability thinktank Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE) estimates that “moderate” policies could reduce emissions by 42 per cent by 2030. More ambitious policies promoting deep renovation combined with renewable energy targets could cut emissions by 60 per cent, according to BPIE’s analysis.

The OECD has recommended a number of actions that policy-makers can take to tackle these cross-cutting challenges and make housing both greener and more accessible. First, investing in building green social housing, and second, subsidising the retrofitting of the existing housing stock. More investment in social and affordable housing brings the dual benefit of protecting low-income or vulnerable households, while directly expanding the housing supply, thereby alleviating upward pressure on house prices. Oliver Rapf, executive director at BPIE, argues that, “There should not be a distinction between green and grey social housing. All public funding should support the green transformation of society, and a large share should be dedicated to vulnerable groups in society.” Regarding the public investment into retrofitting, Rapf highlights the potential for wider economic stimulus: “The right mix of financial support schemes, well-designed for specific target groups, can trigger private investment by a factor of 5 to 10 for every euro spent from public funds.”

The cost of living crisis as well as the fossil fuel import dependencies highlighted by the war in Ukraine add further impetus for national governments to invest, and set appropriate frameworks for private sector investment, in affordable and sustainable housing. “High energy prices, while weighing on purchasing power, also increase the return on energy-saving investment. The question of funding this investment is very important to address, starting with low-income, liquidity-constrained households,” says Cournède.

At the European level, the main policy drivers under the EU Green Deal include the Renovation Wave strategy that aims to double the renovation rate. Although it is not binding legislation, the Renovation Wave sets priorities (including decarbonisation of heating and cooling and tackling energy poverty) and highlights available European funding for renovation. Connected to this, the EU-level Affordable Housing Initiative is creating 100 lighthouse projects based on small district approaches, ensuring social housing providers also benefit from the renovation wave.

Another key policy instrument is the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), the keystone of EU building legislation, a revised version of which is currently being debated in the European Parliament. The revision includes drivers such as “minimum energy performance standards” regulating the energy use in buildings. Such standards are already proving effective in driving decarbonisation in several buildings sectors in the UK and the Netherlands, for example by requiring rental properties to achieve a reasonable energy performance. Advocacy groups such as Housing Europe, however, warn that these tools should be used with care to avoid worsening the affordability crisis.

Stronger regulation can change the game

Green Party Member of the European Parliament, and rapporteur for the EPBD revision, Ciarán Cuffe is confident that the draft legislation will help to set a strong regulatory framework for affordable and sustainable housing.

“We’re looking to expand the incentives for investing in social housing by ensuring that member states implement minimum energy performance standards that target the worst-performing buildings and low-income households”, explains Cuffe.

This ambition must be matched by the member states. National governments will have to oversee the increase in energy performance standards of their building stock as well as provide targeted funding schemes for vulnerable households and reporting on the measures they are taking to decarbonise the building stock in their national building renovation plans.

For Cuffe, the role of finance in the draft revision is vital: “We want the member states’ reporting (via the national renovation plans) to include the measures that they are undertaking to attract financial investments from the private sector.” Using public finance to offer subsidies, zero-interest loans, and tax credit schemes to stimulate the renovation market have proven effective in triggering private investment, with public-private investment ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:83 for every euro of public money spent. Article 15 of the EPBD sets out the financial incentives for renovations and references existing EU-level funding streams include the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Social Climate Fund, and the European Regional Development Fund.

Ambition at the European level must be matched by member states.

Cuffe reckons that major players in public finance are gearing up for large-scale financing of retrofit. He says: “My office has been in touch with both the European Investment Bank (soon to be rebranded as the “Climate Bank”) and the European Central Bank in order to get an understanding of the financial institutions’ perspective and I believe that there is support for increasing renovations across Europe once we have a solid regulatory framework in place.”

The view that legislation has a crucial role to play is shared by Dominic D. Keyzer, global sustainability lead at Dutch multinational and global financial player ING. Keyzer and his team are responsible for the global integration of ING’s sustainability strategy into retail banking and ING’s sustainability activities across 25 markets. “ING has been actively involved in the sustainable housing agenda since at least 2017,” says Keyzer. The bank offers green mortgage loans in the Netherlands and Poland, as well as eco-renovation loans in Belgium. In Germany, ING is collaborating with the German state-owned KfW, the world’s largest national development bank, to deliver a new set of KfW subsidy programmes with a focus on financing energy-efficient real estate.

Clearly, for overall decarbonisation of the residential buildings stock; “there is already significant interest from banks – and commitment – as we ourselves are aiming for net zero,” says Keyzer. “However, without firm regulation to enshrine the EPBD and other Green Deal targets, that can encourage homeowners towards sustainable renovations, we predict that customer demand will not deliver the required change in the next few years. Regulation can play a key role in moving the demand, and that would be a game-changer.”

Local and national initiatives are blazing a trail

Many worthwhile programmes supporting the provision of sustainable and affordable housing are already operating at local and regional level across Europe . In Ireland, the Better Energy Warmer Homes scheme has provided free energy upgrades to households in receipt of social welfare payments since 2000. The Renovatieversneller (renovation accelerator) in the Netherlands has a budget of 100 million euros (2020-2023) and provides subsidies and technical support to social housing providers. In Denmark, a fund established in 1966 finances renovation and new builds for social and affordable housing. These initiatives are in part due to a long-term trend of national governments allocating more housing responsibilities to the local level, coupled with local governments’ rising ambition for sustainable and affordable housing, particularly in city administrations where housing shortages are most acute.

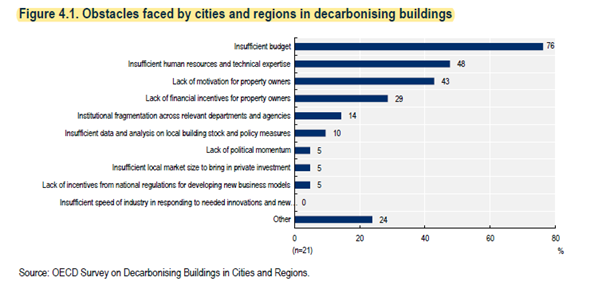

The OECD report Brick by brick notes that, “Over the last 30 years, many national governments have implemented policy reform to allow local governments to assume a larger role in developing, coordinating and implementing housing policies, including those focused on the social housing stock and affordability challenges.” Subnational governments play a critical role in the provision of social housing along with responsibility for the bulk of housing expenditures. But with the overall decline in public investment in housing, local government may not be able to access adequate financing from central government to be able to respond to local housing needs. According to the recently published OECD report, Decarbonising Buildings in Cities and Regions, these administrations are often more ambitious than national government when it comes to sustainable buildings. The report highlights that, “88 per cent of the cities and regions surveyed demand higher energy efficiency standards than the national level in building energy codes, and 25 per cent even call for a net-zero energy level”. However, capacity gaps remain, with lack of finance identified as the leading challenge (see figure below).

It is clear there is a need for more coherent, streamlined action between national and subnational governments, as well as within national governments as in most countries housing policy involves several ministries. In Europe, the affordable housing sector ranges from 4 per cent of the national stock (in Hungary) to 35 per cent in the Netherlands, with the public, cooperative, and social housing sector forming an average of 11 per cent of the total housing stock across the bloc, making it a key player in driving the market demand for sustainable housing.

Against this disparate background, “we see that collective solutions are required to create change,” says Keyzer. “That’s why we intend to partner and innovate with other actors in the housing market.” As the primary bank for larger housing associations in the Netherlands (where 1.2 million homes are owned by housing associations), ING is providing advice and 50 million euros in low-cost financing for retrofit via the “Warmtefonds” (national heat fund).

From crisis to lasting change

The war in Ukraine adds yet more momentum to the broader decarbonisation agenda due to the political necessity of reducing Europe’s dependency on Russian fossil fuel imports. As to what this means for prioritising low-carbon housing, Rapf sounds a note of caution: “I definitely observe more political attention on solutions to decarbonise buildings, but I also see an imbalance in favour of certain technologies. What’s lacking is a comprehensive approach which would reduce energy waste in our buildings so that the reduced energy demand could be supplied exclusively by renewable energy. There seems to be a lack of political understanding that energy conservation and growth of renewables have to go hand in hand.”

The housing shortage, rising costs of living, and the need to limit fossil fuel import dependency together make a powerful case for radical public intervention.

From a political perspective, Cuffe is unequivocal: “All the money we spend on fossil fuels helps fund Putin’s murderous war. This is the opportunity to make the switch towards a renewables-based economy both from an environmental and moral perspective. More fossil fuels is not the answer to a crisis made worse by our over-reliance on fossil fuels. The best way to isolate Putin is to insulate our homes.”

Every crisis contains within it the seeds of opportunity. The widespread housing shortage, rising costs of living, and the political necessity of limiting fossil fuel import dependency combine to make a powerful case for radical public intervention in the housing market. Aptly described by Housing Europe as “the soul of the Green Deal”, the provision of sustainable and affordable housing is a central component of a truly just low-carbon transition for Europe.